chasing each other with the quickness of thought, and uttering at the same time a shrill screaming noise, like the Swift of Europe, whence in all probability has arisen its colonial name. Sometimes these flights appear to be taken for the sake of exercise or in the mere playfulness of disposition, while at others the birds are passing from one garden to another, or proceeding from the town to the forests at the foot of Mount Wellington.

Think Fast

Rachael Weaver on the swift parrot

Think fast is what my fourteen-year-old son says when he pelts a lemon straight at me from across the room. Left-Handed Lemon is a game I invented decades ago. The rules are not that complicated: you throw the lemon with your left hand and your challenger catches it with their left hand. Throw hard and don’t drop it – again and again – that’s how to win.

Think fast is what my fourteen-year-old son says when he pelts a lemon straight at me from across the room. Left-Handed Lemon is a game I invented decades ago. The rules are not that complicated: you throw the lemon with your left hand and your challenger catches it with their left hand. Throw hard and don’t drop it – again and again – that’s how to win.

I like telling people this game anticipated discoveries about neuroplasticity made famous by Norman Doidge’s international best-seller The Brain that Changes Itself (2007). One of its key arguments is that repeating a task will make your neurons fire faster and, almost magically, you will think and react faster. Left-Handed Lemon started with the exact same premise, only without any of the scientific knowledge or research, case studies or magnetic resonance imaging. If you teach your brain to throw and catch lemons left-handed, my hypothesis went, it will somehow make you smarter.

Think fast is the phrase that came into my head as I stood abstractly scrolling on Instagram in the nowhere place between my freshly made bed and the bathroom. I’d been following the Bob Brown Foundation’s efforts to preserve critical species habitat in the old-growth forests of Tasmania, from the Eastern Tiers and the takayna/Tarkine of the north west to regions south of Hobart. The Tasmanian devil, the Tasmanian masked owl, the giant Tasmanian freshwater crayfish live there – which would all be news to me without the Bob Brown Foundation’s efforts to raise public awareness.

‘Raising public awareness’ is an interesting generic and affectively neutral sort of phrase that belies its underlying purpose of targeting our most intimate hopes and fears to lift an issue high into prominence like a crowd-surfer buoyed by many hands across a mosh pit. Best case: it taps into an emotional, moral and intellectual current that connects us to others and impels some sort of immediate large-scale action. But it hardly ever happens like that.

I had been monitoring the Bob Brown Foundation’s efforts to defend the Tasmanian forests with the same work-a-day interest and anxiety I spread across so many things – tending worries like darkly furred creatures kept in separate hutches. But reading this foundation-member’s heartfelt testimony in a ten-swipe sequence saw my worries escape their allocated boxes and grow. She had been tree-sitting up high in an ancient eucalypt for three days before Police Search and Rescue forced her away so that a logging company could continue chasing short-term economic gains. Soon afterwards she heard the chainsaws revving and soon after that the giant tree crashed down, ready to be woodchipped and exported. Bob Brown and two other campaigners had been arrested the day before – on 8 November 2022 – and charged with trespass.

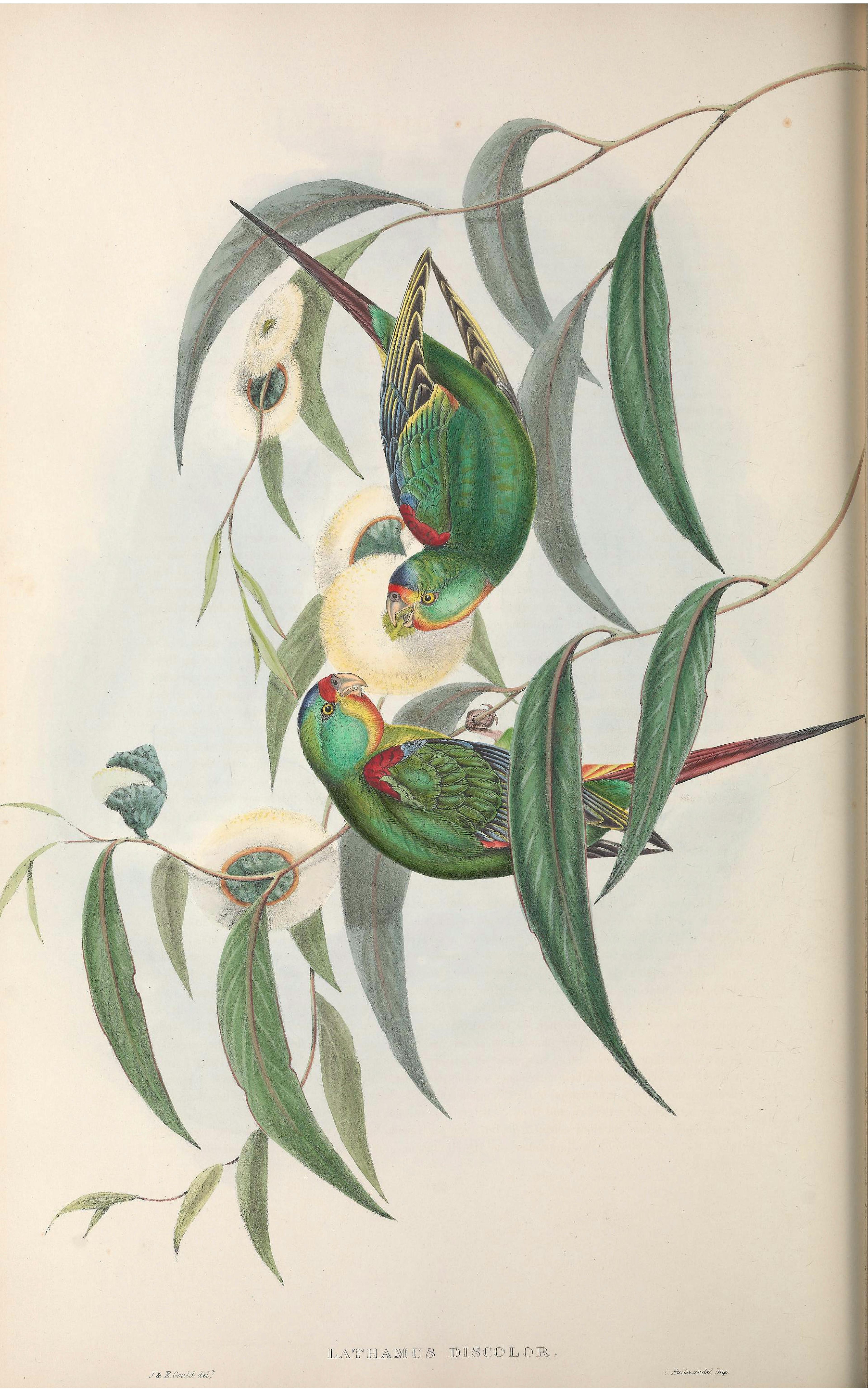

A key part of the foundation’s campaign focusses on the critically endangered swift parrot (Lathamus discolor) because the old-growth forests of Tasmania are the only place this species breeds. If you are lucky, you might also see swift parrots in Victoria when they cross Bass Strait to feed on eucalyptus nectar in the fertile woodlands of the temperate south east. Birdlife Australia’s website notes that these colourful and compelling birds have for many years acted as ‘effective flagships for the broad scale conservation of woodlands, thus benefiting a multitude of additional threatened and declining birds and ecological communities’. So swift parrots are the bright emissaries and chosen ones for fighting ecological devastation. This strategy of deploying iconic, rare and charismatic species to achieve wider biodiversity outcomes has sometimes been questioned, but it is also considered effective because conservation action is closely bound to cultural and social constructions of species.

The foundation’s swift parrot campaign is designed precisely in this way – hosting citizen scientist surveys each weekend to count swift parrots and running a ‘Summer for Swifties 2022/23’ awareness drive. Save the swifties and you’ll save all their creature friends and enemies. I understand why environmental campaigns for species justice use comic-book nicknames as hooks to try to make people care. But they can also seem like predictors of their own failure – as strained and futile as the games of an overworked teacher trying to make a boring lesson fun.

The Birds of Australia, John and Elizabeth Gould, vol.5 (1848). Photo Courtesy of the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

What I felt as I scrolled through the story the foundation member told was only the familiar ache of knowing something really bad is happening in the world and feeling powerless to stop it. Think fast is the phrase that came up, of course, because of the overwhelming urgency of this environmental crisis, and the next one, and all the others that will just keep coming. But it also came from some half-remembered phrase about swift parrots by the celebrated nineteenth-century ornithologist John Gould in his seven-volume study of Australian native birds published between 1840 and 1848.

Instead of getting ready to go out as planned, I went over to look up Gould’s book at the plywood lockdown desk in the corner of my bedroom. ‘Small flocks from four to twenty in number are frequently to be seen passing over the town,’ he writes,

Thinking fast is something this bird embodies in movement – for Gould, at least – leaving behind the dullness of humans with its spontaneous enjoyment of flight. It flies fast through the air because it can. It is the fastest parrot in the world; capable of speeds of up to 88 km per hour, as measured by researchers at the ANU. It is also one of only three migratory parrots in the world, and can make the journey from Tasmania to the mainland in just three hours.

I feel a weird sense of envy and indignation as Gould describes their extraordinary abundance – not only in ‘all the gum-forests of Van Diemen’s Land’, but also ‘in the shrubberies and gardens at Hobart Town, small flights being constantly seen passing up and down the streets, and flying in various directions over the houses’. Gould’s affection for this species is magnified by his enjoyment of a long and pleasurable stay with the Governor, Sir John Franklin, and his wife, Lady Jane Franklin. He notes the Franklins’ support and enthusiasm for his endeavours with his wife, Elizabeth Gould, to record and illustrate the local native bird species – in a kind of holiday snapshot of the contradictions of colonialism.

Gould worried explicitly about the impacts of colonisation and settlement on the survival prospects of the native bird species he so valued and admired. In his book he uses words like ‘extirpation’ freely and designates the ‘white man’ the ‘enemy’ of many unique and beautiful birds. He can see everywhere the threats colonisation brings to species as habitat is cleared and species are shot and killed and eggs are collected and what he terms ‘wars’ are waged against them. Gould’s work is a self-conscious record of what is being lost at the same moment it is being studied, defined, painted and celebrated.

But his account of the swift parrot is strangely oblivious to all of this destruction – as if this bird’s infectious good humour stifled any thought of its demise. He watches it dart about like an arrow, joyfully oblivious to humans. ‘They approach close to the windows,’ he writes, ‘and are even frequently to be seen on the gum-trees bordering the streets, and within a few feet of the heads of the passing inhabitants, being so intent on gathering the honey from the freshly blown flowers which daily expand, as almost entirely to disregard the presence of the spectator’.

Here the swift parrot is understood as part of a built and manicured environment – a fragrant and dreamy place that coheres seamlessly with the nearby forests and betrays no trace of the violence of the Tasmanian War that had seen the systematic removal of the Palawa people from Country little more than ten years earlier. The swift parrot adorns this ‘settled’ landscape and augments human experience, while its most dedicated chronicler and advocate resides comfortably with a figurehead and agent of the imperial structures that drive the relentless colonial expansion and development that will see its habitat decimated.

It was the governor himself who had the power to issue licences to individuals occupying the tracts of forest deemed ‘Waste Lands’ for ‘felling, removing and selling the Timber growing on any such Lands’ under the Australian Colonies, Waste Lands Act of 1842. Alongside the goal of clearing land for agriculture in the country’s most heavily forested colony – which began with the arrival of the first settlers with their sheep at Risdon in 1803 – was a drive to extract timber resources for colonial buildings and infrastructure, for the shipbuilding industry, and for export to other colonies and across the globe.

Distraction soon saw me tracking the early circulation of the prized Huon pine and trawling through histories of the Tasmanian timber industry, learning about how long it took to institute any conservation measures and how these were often thwarted from the start. The State Forests Act of 1885, for example, allowed for the appointment of a Conservator of Forests in Tasmania. From 1886 to 1888 G. S. Perrin held the role, but his inexperience, combined with a rambling communication style, meant he made little impact. He was replaced by an ex-Member of Parliament, W. H. T. Brown, who also found it difficult to change things. He returned to parliamentary duties in 1893, leaving this post unfilled for the next twenty-seven years.

By now I was tipping head-first into this understory and keying in search after search to try to find out more about W. H. T. Brown’s background, priorities and contributions to forest conservation in Tasmania. But all my search words and phrases kept returning me to Bob Brown and all the crises of the present day – as if to highlight how little progress has been made. I was glad of the dead end really, and pushed the forests aside to resume hunting for the swift parrot in a colonial archive of digitised paper and ink that recognises them by at least a dozen different names.

My searches fanned out through Trove’s newspaper database, which works like a set of well-trained neurons to deliver information fast. Lathamus discolor – its Linnaean binomial designation – honours the naturalist, physician and author John Latham who gave scientific names to many of Australia’s best-known native bird species without leaving England’s shores. This Latin name means ‘Latham’s bird of many colours’. Using it as a search term returns the kinds of historic newspaper articles that focus on natural-historical description, giving precise details about the patches of colour that differentiate this species from its many colourful brethren.

Other names and other sources bring more anecdotal encounters, sometimes with a splash of uncertainty about the precise identity of the species being described. One thing they show is that in the nineteenth century the swift parrot’s regular habitat extended much farther than it does now. It was a common visitor to South Australia, and it was seen in abundance through Victoria to the Wide Bay District and Richmond and Clarence River Districts of New South Wales. The ornithologist and museum curator Alfred J. North gives an account of this broad habitat in his Descriptive Catalogue of the Nests and Eggs of Birds Found Breeding in Australia and Tasmania (1889).

Articles by bird watchers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries agree. One 1887 piece in the Adelaide Observer about donations to the taxidermy department of the Adelaide Museum, for example, mentions the swift parrot was ‘once very common amongst the forests upon the plains of Adelaide’. A 2021 National Recovery Plan for the Swift Parrot commissioned by the Australian Federal Government notes the species’ habitat to its fullest extent – encompassing small areas of South Australia, ACT, NSW and even Queensland. But sightings in these places are rare. The report acknowledges that population numbers have continued rapidly to diminish since the publication of a previous swift parrot recovery plan in 2016. It attributes this decline to habitat loss and climate change, together with the ‘previously unidentified threat’ of predation and habitat competition from sugar gliders, which were introduced from the mainland to Tasmania as pets in the mid-1830s and are now considered invasive.

Many nineteenth-century mentions of the swift parrot relate to taxidermied specimens being added to museums around the country – and around the globe. The species was highly valued as a colourful adornment to the natural history collections that recorded and sought to understand and memorialise it. Killing a native species to preserve it in death is a complex cultural tribute that simultaneously forecasts or acknowledges a systemic failure to preserve it – and its habitat – in life.

Fascination with the swift parrot – even as expressed by bird lovers – could sometimes take unexpected and visceral turns. The celebrated ornithologist Archibald Campbell looked back on his boyhood in the leafy Melbourne suburb of Malvern in Nests and Eggs of Australian Birds (1901), recalling an ‘irruption’ of hundreds of this species when the red-gum trees were in blossom – probably in the late 1860s. With a group of other boys from the neighbourhood Campbell shot ‘a string of them’ to bake in a parrot pie – a popular dish prepared by settlers from the beginnings of colonisation, sometimes out of necessity and sometimes out of a genuine appetite for the local ‘game’. One 1851 article in the Sydney Morning Herald about birds as a natural resource notes the ‘truly astonishing’ numbers of parrots trapped in the suburbs of Sydney by local ‘juveniles’ and adds that ‘this kind of game is by no means despicable, for parrots, large and small are capital eating, either curried, stewed, or in a pie’.

An early settler from Southampton, Mary Thomas, describes preparing parrot pies to celebrate Christmas in her diary of life in the newly established colony of South Australia in 1836. The Scottish settler Katherine Kirkland, who lived at Trawalla in Western Victoria for two years in the mid-1840s, also writes of parrot pies as Christmas fare. In her diary, Life in the Bush, Kirkland uses the term ‘parrot’ broadly to encompass cockatoos and other species. I’m somehow heartened by her interest in ‘bush food’ and by the curiosity and pleasure she seems to find in watching the local Wathawurrung people prepare birds to eat by roasting them in hot ashes.

Reading these accounts, I wonder idly how many birds Archibald Campbell considered a ‘string’ and what number of swift parrots might be needed to make a standard pie. With only around three hundred remaining in the wild today (according to some estimates), I try to calculate how many of those savoury colonial delicacies they would fill. The answer is probably twenty five. It seems surreal to say that later editions of the British mainstay Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management embraced some ‘typical’ Australian culinary fashions – including a recipe for parrot pie which called for a dozen parrakeets simmered with ham and beef under a golden crust.

As well as mapping the extent of the swift parrot’s original habitat range, colonial newspapers also documented the gradual contraction of its migratory patterns as more and more forests were cleared. A regular nature columnist for the Evening Journal, under the signature ‘M.S.C’, recounts having found an injured swift parrot near Adelaide in 1854 that died within a short time of its rescue. This observer also reports seeing ‘a good number’ around Burnside near the Adelaide foothills ten years later – but notes that his only encounter after this was with caged specimens in the London Zoological Gardens.

The swift parrot was a sought-after aviary bird both domestically and internationally. It became swept up in the thriving wildlife trade that saw species circulating the globe as objects of scientific study, curios, pets and live exhibits. Swift parrots were featured in the Paris Exhibition of 1855 and a wide range of Australian native bird species, especially parrots, were exported live to England and elsewhere by exotic wildlife dealers such as the famous London-based merchant Charles Jamrach. These numbered in the tens of thousands per shipment throughout the 1860s and beyond, but the crowded and unsanitary conditions of the cages in which they were kept meant that many did not survive the journey.

An 1873 article reprinted from the London Spectator describes a remarkable display of one thousand and sixty-three individual bird species from Britain and across the globe at the Crystal Palace in spring that year. They were surrounded by plants and flowers and ‘so arranged that the Show looks like a Bird City, with a brilliant garden suburb, and a great floral pyramid for its Hotel de Ville’. The article gives special attention to the wide variety of Australian parrots (‘Where did they catch him? What had he seen?’) and it is most likely that swift parrots were among them. ‘Here are innumerable parakeets’ the commentator says,

with warm flashes from the Australian skies yet upon their wings, treasures of colour about them, disclosed with each movement. It is strange to think of the lonely, vast places whence these bright creatures come, of the awful desolate tracts, the changeless trees, the wealth-laden, solitary earth, with many a secret yet close hidden, notwithstanding the widespread rifling of its breast, over which their silent flight has past.

Here Australian native bird species are portrayed as bright strangers bearing secrets from an otherwise drab and mysterious place in the Antipodes that many urban spectators could still hardly imagine beyond the clichéd descriptions of trackless wastes and dreary solitudes peddled by European metropolitan print culture.

But the local, colonial-era enthusiasm for seeing Australia’s native species embraced by zoological and scientific institutions, dignitaries, fanciers and aficionados overseas seems to have declined after the first two decades of the twentieth century. An article in Sydney’s Daily Telegraph broadcast its indignation about rampant wildlife exports at the beginning of 1922, arguing: ‘The demand of zoological authorities overseas is dredging Australia of her rare animals and birds. If an amazing exodus is not speedily checked few of the best loved and most wonderous of our birds and marsupials will remain with us in a few years.’

The article focusses on the activities of Australia’s Zoological Board of Control, which had been formed in 1920. Its official remit was to regulate the import, export, and exchange of birds and animals for public exhibition, collection and trade. Unofficially, according to this article, it was also designed to block ‘German activity’ in supplying Australia with birds and animals in the wake of the First World War. The board included curators and agents from zoological gardens across the states with Fred Flowers (the first chairman) and Albert Sherbourne Le Souef (the first director) of Sydney’s Taronga Park Zoo as Chairman and Honorary Secretary.

Within a couple of years, however, the Daily Telegraph was calling the Board of Control an ‘unofficial organisation’ and demanding an enquiry into the vast numbers of birds and animals being exported, what returns were being made on these ‘exchanges’, what kind of payments the ‘agents’ were receiving, and why private individuals as well as public institutions overseas were reported as having direct access to the shipments to stock their domestic menageries. Swift parrots and parrots generally were prominent in the export inventories.

Nineteenth-century colonial Australia revelled in the delight and interest European royalty and aristocrats invested in its distinctive native species. But the 1922 Daily Telegraph article expresses outrage that the Duchess of Wellington was given ‘first choice of the consignment sent to London by Mr Le Souef’. Dorothy Violet Wellesley (née Ashton), the Duchess of Wellington, was a writer and socialite who kept extensive aviaries on her estate, Ewhurst Park, in Hampshire. The central building of ten well-stocked enclosures included a formal ‘sitting room’ in a garden setting for viewing its exotic species in comfort and at close range. 1922 also happens to be the year Wellesley moved to a flat near Hyde Park, leaving her husband and children in order to begin a romance with Vita Sackville-West, as recorded by Sackville-West in her entry about Wellesley for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ewhurst Park, meanwhile, has recently been bought by former Dior model Mandy Lieu, who is in the process of regenerating it into an ‘eco-haven’ and home for a reintroduced colony of beavers.

The 1922 ‘Wild Life Goes Abroad’ article has a genuine sense of urgency: it wants to think fast about the ways Australia values its native species. But instead of focussing on local wildlife’s intrinsic value, it plays out as a discussion of public institutions versus private individuals and the question of financial interest and who can benefit. It points out that New South Wales already had a Birds and Animals Protection Act designed both to prevent species’ export overseas and ‘their continuance in captivity by private persons’ domestically, but – as the article notes – this was entirely at odds with reality.

Tasmania brought in similar legislation in 1928 with the establishment of a seven-member board for the protection of wild animals. Its list of ‘wholly protected species’ includes ‘all Indigenous or exotic birds except those partly protected or unprotected’. The list of unprotected birds is surprisingly long and, almost inexplicably, includes the swift parrot despite all signs that its numbers were already dramatically declining.

I’ve been thinking slowly about Australia’s native bird species for a while now. Thinking slowly comes naturally whenever I try to inhabit an idea, a primary field, an argument. I approach side-on, treating it like some sort of shy animal that will slip away into the wilds if I walk straight up to it. This isn’t the most efficient method. But I am an over-thinker, so thinking takes up (or wastes) a lot of time.

The vagaries of research funding can mean slow thinking gets slower: it stalls and sometimes stops all together with so many other things (mainly work and money) to think about. I lose discipline and work on stuff like this when I should be doing something else. That’s another way of thinking fast but also taking your time. Time stolen from another set of tasks gives both urgency and a feeling of luxury to whatever you are spending it on.

Most people have the same kinds of dilemmas; time to think comes at a price to other areas in our lives. Thinking about a parrot can come out low in a long list of competing priorities and distractions – and anyway, what does thinking, or even writing, about a species do? Instead of running away to join the Bob Brown Foundation or other grass roots environmentalists, I follow news stories about ministerial forest tours and slow deliberations about logging licences, mining companies and tailings dams, and I read articles with titles like ‘Why Do People Fail to Act? Situational Barriers and Constraints on Pro-Ecological Behaviour’.

I try to give myself a sense of urgency by setting arbitrary deadlines and sticking to them. I planned to finish this essay on 31 December 2022, and when Christmas came around, I was still telling myself I would have plenty of time in the lull before New Year. But first thing on Boxing Day thinking fast took on a whole new meaning as we rushed to call an ambulance when my son became seriously ill from an infection that had been secretly working its way through his body. It took several days to accept the reality. I asked for my laptop at the same time I asked for my toothbrush, a book and pyjamas – as if this were some sort of holiday I could get through pleasantly enough by writing about swift parrots while bonding with my son.

In the mornings when my partner arrived and in the evenings before he left, I walked in Royal Park to try to slow down my thinking. In the rippling heat I would make my mind recite the NATO phonetic alphabet and repeat the first twenty elements of the periodic table in time with my steps. I checked on magpies that spread out their wings in the undergrowth; they were only trying to cool down but looked rumpled and damaged among the sticks and dried leaves.

I examined the local plant life and found new ways of following the same paths. Once I heard the clearest, sweetest birdsong – five notes – again and again like a special message. I am not much of a bird watcher so I had no idea what it was. I walked towards the sound, trying to catch sight of the singer and then noticed many others doing the same – all walking silently towards the tall eucalypts. We gazed upwards into the harsh light like people in a film drawn to an alien spaceship.

We were mostly wearing lanyards from the strange never-private world of the hospital where daily life means being at once surrounded by other people and isolated by fear. I was too stuck inside myself to show it, but the bird connected us somehow. It never revealed itself but moved from tree to tree miraculously calling to its followers from invisible vantage points. Of course I knew it wasn’t a swift parrot. But I let myself imagine it might be. I couldn’t record the sound to search for it later because I had left my phone back in the room playing an audiobook – repeating all of the same familiar stories that would get us through the long weeks until good news finally came.

We moved across the park from the hospital to Ronald McDonald House and spent hot days lying on single beds, eating donated sachets of cereal, and gazing from our upstairs window onto the square green gardens below with their tidy lawns, tall eucalypts and leafy European giants. Every morning I watched an elegant woman carefully sweeping the paths beneath the trees and collecting the debris in an orange shopping bag, the sort you get from T2. What was she gathering – seeds? Every evening I watched people picnicking on the grass or lying back and talking on their phones, lazily watching their children climb and swing.

When the day came to leave for home, I woke up at dawn and listened to the new morning sounds outside: distant cars and voices, rustling, tweets and trills. And then I heard the five familiar clear, sweet notes. Four low – two long, two short – and the last higher. I found the right app and leant out of the window to record the ambient sounds of Parkville for a full five minutes, but the bird had gone.