i just want plumbing, art

— Gareth Morgan, ‘the national debt’.

I hate work so / That I have found a way

— Lesbia Harford, ‘I hate work so’.

Our work is made possible through the support of the following organisations:

Louis Klee on poetry and work

Can the analogy between poetry and work help us understand capitalism in the contemporary moment? Is poetry itself a form of work?

i just want plumbing, art

— Gareth Morgan, ‘the national debt’.

I hate work so / That I have found a way

— Lesbia Harford, ‘I hate work so’.

John Forbes sure had a lot of jobs. The epigraph of his 1992 essay ‘The Working Life’ is a single word—‘Work!’—attributed to Maynard, a TV character who would reliably shudder should anyone mention the subject in his presence. Forbes’ essay would certainly make Maynard shudder. ‘The Working Life’ is essentially a CV. Forbes recites his past jobs in order, one by one, but instead of listing useful skills or credentials, he gives us gossip on the bosses’ eccentricities and relishes the less than appealing moments on the job, such as seeing a co-worker ‘standing knee-deep in dog food’. The first job Forbes remembers in any detail was his time digging a sewer near Cronulla. He then worked part-time in the ‘packing line in a dog food factory’, his boss being a ‘nice bloke’ who employed ‘a lot of unemployable Arts students’. Those were the ‘halcyon days for shit work’, he recalls—an example of how, when poets talk about work, things tend to get scatological. Other jobs included a stint as a furniture removalist, all-night shifts at a petrol station, a period at Darrell Lea’s chocolate factory and later making tinsel, another as a porter for Australia House in London, another picking oranges in Greece, and even a post as a builder on the Sydney Opera House.

Perhaps the job that seems the most Forbesian in this list, other than spells as ‘a dole bludger’, was the poet’s time working the nightshift for a souvenir shop at Kings Cross, ‘flogging […] hilariously overpriced junk’. The stuff in the souvenir shop was, he says, ‘beyond taste. Some of it was almost beautiful, especially the landscape tea trays and the native-bird table cloths. The ashtrays were good too as well as those postcards of Sydney at night that make it look like a postmodern metropolis’. While the boss disapproved of Forbes’ refusal to wear the company uniform, observe the no-smoking rule, and his politics (‘Ah, you are just a parlour Bolshevik’, he would tell him), Forbes was kept on because no one could deny that when he did a shift, sales went ‘through the roof’.

‘The Working Life’ rarely pauses this job-by-job description to offer anything much by way of reflection on the relationship between poetry and work. It could be that, as Harry Reid says, the question ‘“can you explain this gap in your résumé” cannot be answered with “I was busy writing poems”’. At one point, Forbes does offer a parenthetical remark for the benefit of future employers who might happen to be reading his essay: ‘my ideal job—given that writing poems is the only really fulfilling work I’ve ever done—would be three, flexible days a week, clearing fifteen bucks an hour, but outdoors rather than in, and with generous smokos. Employers take note’. Mostly, though, ‘The Working Life’ leaves the relation between poetry and work unstated. It is only in the essay’s final line that it gets to the subject: ‘If you’ve read my work, you’ll now see that there is no necessary connection between a poet’s work and his life’.

This may seem like a throwaway line or a summary dismissal, but it’s also a little tricksy. The essay’s title refers to the ‘working life’, but here the distinction is between work and life, while the ‘poet’s work’ refers to writing and not the litany of odd jobs. But perhaps what is most interesting about Forbes’ claim is that he insists not that there is no connection between poetry and work, but that the connection is not necessary. For what is work, for most people under capitalism, other than time spent doing something ‘not out of choice but out of necessity’, performing, in Jasper Bernes’ words, ‘unfree activities in exchange for money’? The casual denouement to Forbes’ essay is compelling because he resents exactly what waged labour stands for in capitalism—a connection based on necessity. Poetry, absent in his essay, is what escapes. In this way, Forbes raises a question that has long exercised poets in Australia: what is poetry’s relation to work? Or, to put it somewhat more extravagantly, can the analogy between poetry and work help us understand capitalism in the contemporary moment? Is poetry itself a form of work?

In exploring these questions, this essay takes inspiration from Jasper Bernes’ 2017 book The Work of Art in the Age of Deindustrialization, which examines how poets like Bernadette Mayer, Wendy Trevino, Fred Moten, and Sean Bonney ‘respond to the world of work, recasting it, critiquing it, celebrating it, or constructing alternative social arrangements from it’. Bernes’ book is filled with insightful analysis of the relationship between political economy and avant-garde poetics in English, but at times I almost felt sorry for him that Australian poetry lay beyond the book’s remit. For Australian poetry provides some of the most fascinating and complex responses to the world of work. This essay, which flits—sometimes fleetingly, sometimes only slightly less fleetingly—from Forbes, Lesbia Harford, Pam Brown and П. O. to Gareth Morgan, Siân Vate, Astrid Lorange, Harry Reid, Ursula Robinson-Shaw, D Perez-McVie, Elena Gomez, Alison Whittaker and others, aims to sample something of the immense creative energy that Australian poetry draws from its attentiveness to the working life. My focus is particularly on Forbes, the directors of sick leave, and Lorange; I examine how they subvert and reimagine Australia’s labourist legacies in neoliberal times. Of course, there are plenty more relevant poets and poems than I could possibly mention here. Work is everywhere in Australian poetry and an essay can’t be everywhere. My hope is that this essay might act as a tiny commonplace book, gathering instances, and in this way invite wider reflection on the poet’s work and the working life in Australia.

‘The Working Life’ is an amusing place to begin, but it would be a mistake to look for answers in an essay alone. Forbes is a poet, after all, and his poetry should be our focus. It is even possible to unfurl the entire economic and political landscape of Australia from a single of his poems, as Meaghan Morris does in her landmark book Ecstasy and Economics(1992). Morris examines ‘Watching the Treasurer’ (1986), a poem best-known for a simile: the bottom lip of Paul Keating, then treasurer of Bob Hawke’s Labor government:

trembles and then recovers,

like the exchange rate under pressure

buoyed up as the words come out—

elegant apostle of necessity, meaning

what rich Americans want, his world is

like a poem, completing that utopia

The treasurer’s world is like a poem because it is a utopia made of words. Commentators at the time fixated on his words, his ‘panache and style’. ‘Keating makes economics sexy’, they declared. Morris is also fascinated by this rhetorical power. She argues that, by mixing ‘gutter invective (the working class “boy from Bankstown” story) and economic jargon (the “corporate” story)’, Keating cast a kind of spell. But Forbes’ poem also works with words and likenesses, collapsing the treasurer’s lips into their economic consequences, mimicking and outdoing his rhetorical bravura. Morris takes this as Forbes’ way of posing the question: ‘if Paul Keating’s world is “like a poem”, what can a poem be like?’ At the time, this was no idle question. Keating’s ‘economic rationalism’, as the Australian media then called his neoliberal reform agenda, broke radically with the country’s political and economic foundations. ‘[F]or all its modern history’, as Morris puts it:

Australia has been governed by […] “labourism,” a social contract upheld in various forms since 1904, [which] exchanged trade protection and currency controls for a state-regulated wage fixing system and compulsory arbitration; as a capital/labour deal for redistributing national income primarily between white men, labourism was sustained by a massive immigration policy legitimated and administered on racist principles until the 1960s—but by forms of multiculturalism thereafter. So the process of internationalizing the Australian economy has had a devastating intellectual (affective, ideology) as well as social effect; as the political alignments of a century slowly begin to shatter, even those “new social movements” most critical of the history and practices of labourism—feminism, anti-racism, environmentalism—find themselves recast by its decline as “entrenched” and “vested” interests now obstructing radical change.

Keating’s wide-ranging program of economic reform took apart the labourist framework piece by piece and replaced it with a deregulated economy integrated into the global free market. Productivity became ‘a value to be extracted in all activity from manufacturing […] to writing poetry’, which makes Forbes’ poem more than a little recalcitrant. Not only does ‘Watching the Treasurer’ fail to offer much in the way of economic value—hence the need for all the poet’s jobs—it also contains a subtle play on the notion of value itself. Morris spells it out: the poet observes how the ‘elegant apostle’ of market value draws his charisma from an earlier kind of value, the cultural values of labourism that he was in the process of dismantling.

It may seem that this has little to do with poetry, but many of the canonical works of Australian literature have themselves been bound up with the values Keating evoked: the ‘workingman’s paradise’ of labourism. This is an insight of Carol Jenkins, when she seeks to counter the ‘accepted wisdom […] that Australian poetry has been built on landscape’ with the claim that it emerged from the ‘forge of work’, or of Douglas Stewart, when he remarks that Australian poetry ‘doesn’t come out of the university—it comes out of a quarry’. Though not literally forged or quarried, Australian poetry has had a significant relationship to late nineteenth-century labourist struggles, one set in amber by Henry Lawson’s ‘The Shearers’ (1901) when he sings of ‘mateship born […] / Of toil’. In venerating hard work, larrikin roguishness, and blokey solidarity, Australian poets helped fashion a vernacular liberté, égalité, fraternité—an ethos that was, in its most canonical and nationalist forms, explicitly coded as masculine and white, or as Lawson adds in ‘The Shearers’: ‘And though he may be brown or black, / […] The mate that’s honest to his mates / They call that man a “white man”’.

For all this, the question of how writing itself relates to labour remained a troubling one. It took on pressing and complex forms for writers who did not fall into the privileged category of the white man, but it pestered even those who did. Take the phrase that opens Joseph Furphy’s Such Is Life (1903): ‘Unemployed at last!’ The writer is a deviant, cast out from the world of work (and perhaps also from the norms of masculinity). He enjoys, in the words of Michael Wilding, both ‘the relief from work, while at the same the prospect of poverty and hunger’. In the place of necessity, the writer has the freedom to reflect on his own imminent immiseration, and yet Furphy also suggests that the existence of the document we are reading—Such Is Life—itself depends on this difficult freedom from work.

Writing hasn’t lost its strangeness in the years since. In his poem ‘The Instrument’ (1997), for instance, Les Murray responds to the question ‘Why write poetry?’ with: ‘For the weird unemployment […] / For working always beyond / your own intelligence. For not needing to rise / and betray the poor to do it’. For the most part, Murray was saved from the prospect of poverty by funding from the Literature Board, which could make the whole idea of weird unemployment look, as П. O. puts it, like ‘the arrogance of those that can truly rigmarole away their hours AND make money—a kind of Aristocracy’. But there is an ambivalence in the phrase ‘weird unemployment’, one that is interesting when read alongside one of Murray’s early essays, ‘Patronage in Australia’ (1972). This was not so much an essay as a manifesto which Murray claims to have had ‘some effect on ALP policy in the arts’ during Gough Whitlam’s term in office. It suggests that any real political solution to the precarious labour conditions of the writer entails a broader system of universal basic income. The problem, as Murray sets it out, is that ‘unemployment’ and ‘misemployment’ are equally disastrous for the writer. The unwaged writer is in a position no better than the writer who receives a wage from ‘some other, often ludicrously alien, job’ to writing—a situation that Murray deems as ‘simply inefficient’ as demanding that ‘an engineer […] earn his living as a haberdasher and design bridges in his free time’. But Murray also recognises something obstinately odd about poetry: if we examine this activity closer, we find it is ‘not a job, but is work’. This may seem a little riddling, but the difference hinges on the fact that the poet cannot effectively bargain by denying their labour. For Murray, the ‘inability to strike’ demonstrates that poetry is an intrinsically fulfilling activity, a model ‘of work fit for humans to engage in’. In this utopian mode—one of ‘perhaps extravagant hope’—he claimed that solving the weird unemployment of poetry is tantamount to guaranteeing just remuneration for all forms of intrinsically valuable doing and making.

One obvious issue with Murray’s essay lies with the idea of ‘misemployment’. The poet who works an ‘alien’ job to writing is, in at least one crucial sense, very different to the fantasy of the engineer with a day job in haberdashery. No engineer makes bridges about haberdashery, but a poet can make poems about work. For all its miseries, ‘misemployment’ has yielded some of the most significant poems written in Australia, among them Lesbia Harford’s lyrics of factory work. In poems such as ‘Buddha in the Workroom’ (c. 1917), Harford achieves a rare equipoise: a lull in the roar of employment, a ‘dream’ tightly worked into the lyric’s metric ‘scheme’:

Sometimes the skirts I push through my machine

Spread circlewise, strong-petalled lobe on lobe,

And look for the rapt moment of a dream

Like Buddha’s robe.

And I, caught up out of the workroom’s stir

Into the silence of a different scheme,

Dream, in the sun-dark, templed otherwhere,

His alien dream.

In the final line of each stanza, metre’s tangled labouring (its ‘caught up out of’) lets up. For a ‘rapt moment’, we are somewhere beyond work and poetic form. But as Ann Vickery notes, the ‘dream’ in Harford’s poetry can only be understood by taking her political commitments and queer desires into account. She was a devoted leftist activist and member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), or the ‘Wobblies’, an organisation that aspired ‘to build an industrial union movement (One Big Union) that would unite the entire working class, irrespective of sex, race, age, skill or culture’. In Harford’s lyrics, too, the ‘sexuality of the factory girl’ is always getting tied up with ‘the political objectives of the Wobblies’, Vickery writes. Harford’s lyrics of the factory do not simply critique the world of misemployment or ‘sing of commerce dryly’. They present the factory as a place of desire, the ‘material out of which a better world might yet be constructed’, as Jeff Sparrow argues. But poetic world-making is a complex endeavour. In the ‘Work-girls’ Holiday’, for instance, learning to escape the regimented time of necessity seems to depend, in a cruelly circular logic, on already having the idleness that one might gain through that escape:

Perhaps if I had weeks to spend

In doing nothing without end,

I might learn better how to shirk

And never want to go to work.

Unlike Furphy, where writing manifests the freedom from work, Harford’s factory lyric says: ‘Unemployed if only!’ She posits this counterfactual from within the world of work, as a worker speaking to other workers in the lyric’s compressed and explosive form. In this way, her poems announce an ‘otherwhere’, an impossible freedom where it will finally be possible to free oneself.

In the place of ‘weird unemployment’, this is poetry as ‘unusual work’, to borrow a phrase from the anarchist poet П. O. From 1978 to 1983, a group of poets that included П. O., thalia, Jas H. Duke, jeltje, cathy johns, and barry mcdonald, edited 925, a magazine which championed the poetry of ‘misemployment’, publishing poems about everything from trucking to typing, hospitality, unwaged housework, unemployment, and teaching. 925 was led by the conviction that it is impossible to separate ‘the “productive process” (“work”)’ from art; it was ‘poetry for the workers by the workers about the workers’ work’. Like Harford’s lyrics, the poems in 925 are written by and addressed to workers; the magazine itself was distributed through the workplace. As П. O. recalls, 925:

was NOT done for any kind of MONETARY consideration or advantage in fact it is quite telling that the “professional” poets in Australia did NOT submit or subscribe to the magazine i take it that their poems had some kind of monetary value and contributing to a rag like “925” unworthy of their labour […] “925” came out of our pockets and we lived off donations (except when placed in bookshops) and altho the contributors “worked” and wrote about their “work” their “poetry work” was an act of self-defence, and defiance. It is quite telling that when we sent Katrina Passoni who worked in a chicken abattoir some money out of our own pockets to help her through her incredible troubles at work + home she sent the money bac saying we were doing a better job with that money supporting voices + writing like hers.

By resisting the professionalisation of writing and the newly consolidated grant system, 925 turned the idea of ‘misemployment’ on its head: to work a job alien to poetry is not just to refuse to extract monetary value from writing, but to clarify the true, non-monetary value of poetry. The work of creating the magazine thus became a collective way of reimagining work itself. In jeltje’s words, it amounted to the work of building a community that cut ‘across divides of race, class and gender’.

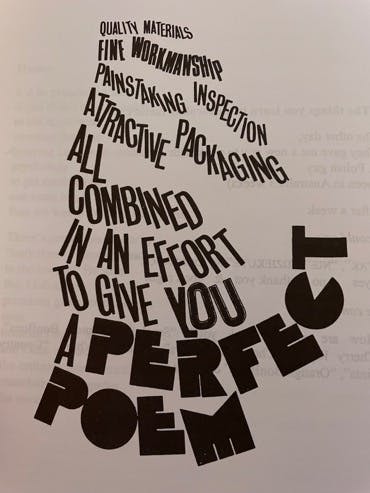

Image: Jas H. Duke, from 925, issue 3. © Estate of Jas H. Duke, reproduced with permission of the estate, with special thanks to П. O.

The poets of 925 were not alone in looking sceptically on the professionalisation of writing. Pam Brown, for example, describes herself in that now ubiquitous genre of publishing—the bio note—as a ‘professional amateur’ or ‘dedicated amateur’. ‘I used that oxymoron’, Brown explains:

as a light-hearted reaction to the notion of having a “career” in poetry. To me an amateur is someone doing unpaid work rather than the derogatory connotation of being inept or not skilled at a task. In the case of poets, the majority of us are not earning much pay, or the equivalent of wages, for our hours of reading and writing, nor for our publications. So, yes, we could be categorised as amateurs though our poems can be complex, skilful, even professional. My experience is that poetry making is a compulsion. There’s not much valour in it.

Brown worked for sixteen years at a life science research library, writing poems on lunch breaks (‘Park lunch’), about work (‘A howling in favour of failures…’), on the commute to work (‘Saxe blue sky (thursday morning)’), and often something in-between (‘On eventually entering the library’). Poetry, for Brown, is not a job, but a special kind of work. To the question in grant application forms—‘how many hours a week do you spend on your writing?’—she would typically answer: ‘24 hours a day’. Her writing bids us to consider poetry as the ‘inadvertent suspension of time’ in the dash between two ‘work’s’, a strange present continuous as in ‘The ing thing’ (2002):

this

shambling

contingency,

(writing a poem) –

work’s,

for me, a sanctuary

from building sites

from something else

from evil duco-scratching

truants

if-not-already, soon-to-be

excluded

from its realm –

work’s

Weird unemployment, unusual work, professional amateurism: these diverging descriptions share a similar doubt. For all the centrality of labourism to Australia’s national culture, it would be difficult to find an Australian writer who would declaim, with Vladimir Mayakovsky, that poetry is ‘a manufacture’ of a ‘very difficult, very complex kind’, as he puts it in his 1926 book How Are Verses Made? In the spirit of poetry put to the service of the revolution, of rhythm with concrete purpose, Mayakovsky takes apart his own composition ‘To Sergey Esenin’ (1926), seeking to pass on ‘some of what seems the most mysterious techniques of this productive process’ to another potential poetic worker. In the wake of a revolution, poetry is work. But when Mayakovsky remarks, for instance, on ‘how much work you must put in just to choose a few words’, it is apparent that the productive work of poetry is different to the alienated, pre-revolutionary labours of the proletariat. Without this revolutionary horizon, the analogy between poetry and work tends to sound strained and presumptuous, or else comic and a little naughty. Poetry can certainly take more ‘time and effort—altogether more work’, as Kent MacCarter puts it, than one puts into ‘mowing the lawn […] or searing a kangaroo fillet appropriately without overcooking it’. But then, MacCarter adds, writing a poem does lack the ‘assumed arduousness’ of work. Poetry is quite simply not toil, and to suggest otherwise is to invite the kind of satiric riposte contained in the US poet Albert Goldbarth’s poetic sequence ‘(Etymologically) “Work Work”’:

‘Oh, I’ve worked hard

before this, I once set lobster traps,’ you always hear

at poetry conventions, ‘but nothing’s as difficult as

Selecting The Proper Word!’ which is usually just bullshit,

such bullshit it’s not even real bullshit, which

weights down a shovel until the trapezoids scream.

In Australia, Goldbarth’s ‘real bullshit’ finds itself inverted in Jas H. Duke’s ‘Shit Poem’ (1981), which begins: ‘I’m in the shit business / I work for the sewerage department’. Duke makes poetry out of working with shit, shit work, but his tone is ebullient. He has no need to be affronted, like Goldbarth, by poets giving the same name—work—to writing a poem and hauling shit in a cattle hangar. To continue a little more with the sewerage theme, we might think, listening to Gareth Morgan’s ‘the national debt’ (2021), that we are hearing the call for a new ‘plumbing art’. But a comma separates the two: there is a minimal partition between writing and infrastructure, between the work of poetry and the honest slog venerated for the better part of a century by the Australian working class.

And yet, something decisive shifted in roughly the time between Forbes’ ‘Watching the Treasurer’ (1986) and his ‘Ode to Karl Marx’ (1993). The dismantling of labourism, and the rise, in its place, of a deregulated, deindustrialised economy incorporated into the global free market has ushered in a new period in Australian poetry. The ‘work of poetry’ has come to mean something different now that work itself has changed, now that the managerial styles of Taylorism and Fordism have given way to the mantras of ‘“flexibility” and “teamwork” […], new forms’, in Bernes’ words, ‘of autonomy and self-management that are really regimes of self-harrying, self-intensification, and interworker competition disguised as attempts to humanize the workplace and allow for freedom and self-expression in work’. We could locate some of the origins of this contemporary moment in Australian poetry in ‘Ode to Karl Marx’, an early example of dolewave poetics written against the backdrop of deindustrialisation and mass unemployment. An ode—that poetic mode of ‘praise or commemoration’ which is always speaking to entities ‘who won’t or cannot answer back: the wind, a corpse, a concept, a god’—has, as Anahid Nersessian remarks in her wonderful book Keats’s Odes (2021), a certain ‘sweetness’ in the sense of ‘sweet talking’. In his many odes, we find Forbes sweet talking death, doubt, Cultural Studies, and Cambridge poets, and yet it is difficult to think of ‘Ode to Karl Marx’ whispering sweetly to its addressee. ‘Ode to Karl Marx’ is a poem that has seemingly decided ‘self-conscious bitterness / is best, besides lust or a // detached disgust’. The collapse of the Berlin Wall appears here in the bathetic form of a dishevelled, slumped cake, but Forbes’ poem has no bathos in its literal sense, as ‘the art of sinking’. Instead, everything is speeding up without progressing, turning and turning, as the poet looks on (the scene might bring to mind Keats’ ‘Ode on Indolence’). He begins with Marx’s truth:

that doesn’t set us free—

it’s like a lever made of words no one’s

learnt to operate. So the machine it once

connected to just accelerates & each new

rap dance video’s a perfect image of this,

bodies going faster and faster, still dancing

on the spot

The problem is not with Marx’s truth, this ‘lever made of words’, but with the fact that no one knows how to operate it. But what is Marx’s truth, exactly? In its most succinct form, it could be something like The German Ideology’s ‘From each according to ability; to each according to need’, which finds a neat, contemporary variant in Aaron Benanav’s Automation and the Future of Work (2020): ‘According to this perspective, abundance is not a technological threshold to be crossed. Instead, abundance is a social relationship, based on the principle that the means of one’s existence will never be at stake in any of one’s relationships’. The decisive failure of the communist experiment in its Soviet form has not falsified this idea, at least not for Forbes’ ode. No, the problem is that Marx’s idea still awaits its true workers. Without anyone who knows how to operate this vast machine for coordinating abilities and needs, the global economy has become a spectacle of grotesque acceleration.

It is here that ‘Ode to Karl Marx’ offers a distinctive response. The poet presents us, as Duncan Hose notes in his much-anticipated study The Pursuit of Myth in the Poetry of Frank O’Hara, Ted Berrigan and John Forbes (2022), with a ‘picture of himself doing nothing, except his nothing has something to it; the grace of reflection, of thought, of empathy, and of turning all this into a poem’. But this is an uneasy place to be, in this meantime, with nothing much to do. Forbes’ makes a thought experiment out of it: he invites us to imagine an ‘inoperative community’ of bludgers and shirkers, in which poetry is purest form of bludging, an Australian equivalent to Walt Whitman’s ‘loafing’. (This is all very ironic, of course, but inverting the ‘working man’s paradise’ into a utopia of bludgers also risks preserving the exclusionary aspects of labourism: a white man, a citizen of Australia, can shirk and reasonably expect to receive some unemployment benefits and even a certain esteem for his deviancies, but bludging among those who don’t fall into this category has often been perceived as a dangerous and pathological aberrance). This plays out in a single sentence, in which Forbes puts the word ‘work’ to use in three different ways:

At the moment tho’ this set up

works for me, being paid to sit and write &

smoke, thumbing through Adorno like New Idea

on a cold working day in Ballarat, where

adult unemployment is 22% & all your grand

schemata of intricate cause and effect

work out like this:

The poem is written on a ‘working day’, but is the poet working? He is not really one of the adult unemployed because he is lucky—the situation is ‘working for him’, which is to say, the concealed labour of others has made it possible for him to sit and smoke and write. Writing here is an activity virtually indistinguishable from sitting or smoking; it is the immaterial work of telling us ‘how things work out’. And what the poet foretells is a scene that, like Forbes’ The Stunned Mullet (1988), plays on the state of muteness:

take a muscle car &

wire its accelerator to the floor, take out

the brakes, the gears the steering wheel

& let it rip. The dumbest tattooed hoon

—mortal diamond hanging around the mall—

knows what happens next. It’s fun unless

you’re strapped inside the car. I’m not,

but the dummies they use for testing are.

What lends this conclusion its unusual intensity and vehemence is that the reader, much like testing dummies and the dumbest hoons, is unable to speak: strapped into the inexorable syntax of Forbes’ poem, we are stupefied, pushed on by its imperatives, hurling towards the finality of its final end stop, enclosed within the inevitability of a sudden rhyme (‘car’, ‘are’). The poet is a bludger who has escaped the necessities of our world, but also a meddler, someone who uses their unique and fragile freedom to return and tell us how it will all work out. The stupefied reader is bestowed with this difficult knowledge. If we happen to be thumbing through Walter Benjamin like a celebrity gossip magazine, we might say that the only hope left is for a revolution in the sense of an ‘attempt by the passengers on this train—namely, the human race—to activate the emergency brake’.

I have spent some time on ‘Ode to Karl Marx’ because I believe this poem anticipates the concerns of a new Australian poetics. Today Australian poets are experimenting with the relationship between poetry and work with remarkable vigour. This is evident across the board, among poets of very different styles and sensibilities. Astrid Lorange, whose Labour and Other Poems (2020) I examine below, already captures something of this in her essay ‘The Work of Poetry’ (2022). She compares Elena Gomez’s Body of Work (2018) to Alison Whittaker’s Blakwork (2018) in the hope of shedding light on ‘the indivisible history of colonization and capitalism, and the way that the very idea of Australia as a nation emerges from the twin logics of settler sovereignty and market economy’. In the joke of Gomez’s title, Lorange finds ‘a body at work, in work, out of work’; in Whittaker’s collection, she focuses on ‘the ongoing and endless work of surviving and having survived colonization’, what Natalie Harkin elsewhere describes as ‘the labour of Indigenous poets past and present, our dreamt-up hopes for work yet to come’. Lorange is not alone in mapping out the theme of labour in contemporary Australian poetry. Kyle Kohinga, for instance, elucidates the political stakes in Lionel Fogarty’s 2016 poem ‘Never Worked’, with its riveting opening—

He wave his fingers saying he’s a worker

Work to the breeze off pride,

Word winner made heat powers run.

Work together in sunshine machine society

—while Julia Clark compares how Ali Alizadeh and Melinda Bufton write ‘into and around capitalism’ and labour in an essay for Cordite. Essays such as these prime us to see how labour is everywhere in recent Australian poetry—in, say, the satirical turns and unexpected tenderness of D Perez-McVie’s ‘The Deliveroo delegate’s day off’ (2018), or in Siân Vate’s ‘Workplace Injury Compensation Form’ (2017), which plays with administrative language and even hints in its title at a poetic form of compensation for the injustices of the workplace.

In addition to these poets, one of the most significant poetic responses to the world of work in recent years has been from a group of writers associated with sick leave, a Melbourne-based reading series co-directed by Ursula Robinson-Shaw, Gareth Morgan, and Harry Reid. The reading series, as Morgan explains, was named in honour of ‘the naughtiness of calling in sick when you weren’t (but then again, we all ARE sick, right?) and also in honour i suppose of the fact that workers fought for the right to sick leave’. In brief, ‘sick leave is bludging, poetry is pulling a sickie’. If we were to focus on the recent work of the series’ directors (Morgan and Reid have already been reviewed together by Rachel Schenberg), then they seem to pick up where ‘Ode to Karl Marx’ left off. For starters, some of their day jobs wouldn’t be out of place in Forbes’ ‘The Working Life’: Morgan’s chapbook Dear Eileen, (2019) was inspired by his time working as a postie; Robinson-Shaw published her chapbook YEARN MALLEY (2022) while a PhD candidate at the University Melbourne; Reid’s debut collection Leave Me Alone (2022) announces itself, if not as a full-blown ‘receptionist manifesto’, then at least as ‘a book about “work” and “labour” […] for receptionists, personal assistants, facilities coordinators, venue managers, customer service officers’. Each of these collections deserves an essay of its own, but they are all rewardingly thought of in relation to political economy, above all the situation of the precariat in the contemporary gig economy—the ‘casualised, uberfied labour force […] people [who] work longer, more erratic or “flexible” hours’, in the words of Dear Eileen,.

In these conditions, equating poetry with work is a less appealing gesture than the thought that poetry might be something stolen from work. Labour, after all, could already be thought of as a form of theft. To return to a celebrated piece of grotesquery, Marx describes capital as ‘dead labour that, vampire-like, only lives by sucking living labour’. If capitalism feeds on the living, then ‘stealing back time’ from alienated work is a little like stealing back life. Following this idea through to its conclusion, Morgan offers this fully-fledged account of poetry’s relation to the working life in Australia:

at xmas my dad’s brothers were creating this imagined australia of workers and bludgers. that’s so central to this country’s conception of itself in my mind. especially in my white family. so in their language poetry would be a form of bludging. which i think is true! […] if i’m being honest, i’m not super attracted to the idea of poetry as work or labour because i am partially stuck in the practical australian mindset of valuing good hard work that makes the ‘world’ ‘better’. […] i value the anti work of poetry as an alternative to having my labour exploited. but like i also want there to be nurses and factory workers and people creating better infrastructure, and baulk at poetry which calls itself important because it has some clever critique of the colonial project, or ‘does the work’ of smashing capitalism, even the work of saying ‘work sucks’… and in this ‘doing the work’ seems to sneer at normies who conceive of hard, virtuous work in australia as inherently good. poetry is a beautiful intervention in a dull and often oppressive world of evil or at best unsexy work. poetry – even bad poetry – is sexy work, about pleasure and following your nose and desire for language. i think its importance is due to it being an intervention, being something other than work.

Dear Eileen, gives a striking demonstration of what this intervention means in practice: a bit like Such Is Life, the chapbook we are reading is the literal product of the evasion of work. These are poems written ‘on the clock’, as the poet is out delivering the post. This makes a poem something like a postie’s letters, ‘which are time, which, i would like to add, in order to be very clear, is what poetry is. time’. What ramifies this with even more delightful complexity is that Dear Eileen, describes the labour of a postie during a time defined by the ‘death of mail’—when, that is, the postal service has been reduced to the adjunct of online shopping—by itself assuming the form of a letter written to Eileen Myles (something explored in more detail by Schenberg). The letter we are reading is a poem for a poet that describes how the postie writes poems on his shifts, exposed to the weathers like ‘a dog, back-sore and lapping up the sad dream of today’.

Reid’s Leave Me Alone was also written on the clock and considers waged time with poetic form. There is a fear that courses through Leave Me Alone—one manifest in the unswerving way that the collection focuses on the thematic of work—that the division between work and not-work might collapse into what Bernes calls a ‘zone of indistinction’, where ‘everything is brought into the circle of work’. Reid’s response to this anxiety is much like that of Wendy Trevino: ‘I write / About work because there’s no escaping / It’. Leave Me Alone relates everything back to work: even if there are ‘a few [poems] about my friends’, we know that ‘work is never too far away’. By letting work appear everywhere, inflect everything, Leave Me Alone presents an alienated world where it is increasingly impossible to carve out time free from necessity.

This is particularly clear in ‘work song’, a poem that responds directly to Forbes’ ‘Ode to Karl Marx’. The poet is not even thumbing through Adorno; they have ‘never read him; / I just work in facilities and it suits me fine’. ‘work song’ begins by promising a clear separation between work and not-work:

it’s simple: it’s either work or it isn’t

resist ‘leisure’ here to describe ‘not work’;

there’s work in leisure and vice versa

Kool Moe Dee spoke of it: ‘to say

that this is not work is ludicrous’,

and he wasn’t talking about a job, he was talking

about rap. he was also talking about hustling,

but really he was talking about life

I keep coming back to it: is this work?

dinner is and isn’t. you are and aren’t,

even when reading this poem. this poem is work

‘work song’ only seems to meander, while performing a virtuosic, ad lib analysis. The poet tests each colloquialism: ‘I am “working” on myself but lazily’; ‘“this year, man”, / we say, “it’s been a real piece of work”’. As the poem moves through these phrases, the initial distinction of work and not-work begins to complicate: ‘in all of us is the capacity for something / great, and for something easy. these are not always two / different things’. As Reid puts it in another poem: ‘work can go to Alice Springs, or / work can go to the shop. work / could also watch a movie, if it wanted’. Against this personified work, Reid sometimes offers the personified poem: ‘staring down the work versus actually doing it, the rat bastard poem / gnawing at the walls says who’d want a desk job anyway’. What defines this personified poem is not so much its resistance to work as its resistance to necessity: a poem can be like work all it wants so long as it doesn’t become necessary, ‘because then it’s homework’. The poem must be lavishly unnecessary, a larrikin strategy or ‘ratbastardedly’ mutiny that flips working hard into hardly working: ‘if the poem has a job it’s to find a way to write / on the clock’; or, as Reid puts it in the best way to destroy an enemy is to make him a friend (2020): ‘I only wrote that last poem so I didn’t have to write what / I’d been paid to’.

A PhD candidate is not a waged worker in the sense of a receptionist or a postie, but Robinson-Shaw’s poems have their own ways of stealing back time—‘my plagiarisms’, as the note to YEARN MALLEY has it. Yearning speaks with borrowed words: ‘I’m the robber of dead men’, which was already a hoax poet’s way of agonising about having accidentally repeated someone else. To call these plagiarisms might make the reader a bit like Turnitin, or at least force them to become conscious of how someone who decides to chase allusions can end up like a university researcher—which is to say, they can end up sharing something with the poet’s day job. One of the dead men reworked in Robinson-Shaw’s poems is Marx, who remarks: ‘the tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living’. For Marx, capital is ‘labour’s own past […] collected in the form of worked matter that impels, determines, and conditions present actions’, as Bernes argues. But if capital feeds on the present, there could be freedom in ventriloquising dead words: the power of a poetic present over the past. And Robinson-Shaw plays freely not just on phrases from the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts (1844) or lines from Emily Dickinson, but even on the gushings of Marx’s early romantic poetry. In 1837, at nineteen years of age, Marx gave up poetry as passionately as he had pursued it, writing to his father: ‘Given the spiritual circumstances lyric poetry was the first resort’. By that point, though, he already had committed some sentimental lines to paper, one of which Robinson-Shaw replays in ‘Sonnet for the Good Meat’ in the chapbook Noonday (2019). It is a line that Marx addressed to his wife, Jenny:

Truly, I would write it down a refrain,

For the coming centuries to see—

LOVE IS JENNY, JENNY IS LOVE’s NAME.

Perhaps it wasn’t one for coming centuries; addressing ‘g’, Robinson-Shaw’s poem describes it as ‘the worst words of your favourite economist’ (contrasting it, toward the end of the poem, with ‘the BEST WORDS / of your LEAST FAVOURITE PHILOSOPHER’, namely, Žižek: ‘“I AM READY / TO SELL MY MOTHER INTO SLAVERY JUST TO FUCK YOU”’). ‘g’ also says that ‘the only way to write a love / poem is to make sure you’ve never / read a sonnet before’, which means it’s too late for ‘Sonnet for the Good Meat’. If love is Jenny, the poem has no choice but to say:

jenny your beauty like a stolen watch

jenny you will read me the news

jenny you will pay for the wine and dine

jenny you will read the new manifestos

jenny you will shelter me from the cold

‘Sonnet for the Good Meat’ is a raucous feat of yearning and debt, where desire does not simply speak in borrowed words or address a borrowed lover, but becomes indistinguishable from borrowing itself.

But why call this borrowing, anyway? If the work of the young Marx teaches us anything, it is to recognise the sensuous force of communism:

The transcendence of private property is therefore the complete emancipation of all human senses and attributes […]. In the same way, the senses and enjoyments of other men have become my own appropriation […] activity in direct association with others, etc., has become an organ for expressing my own life.

Poetry written in this spirit asks us to imagine the unalienated work of what Marx calls the ‘total’ human being: a being who, to paraphrase the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts, objectifies the world not for the possibility of wealth, but for its wealth of possibilities. This sensuous vision of the abolition of private property can spell out, as Nersessian argues, the political potential of poetry’s negative capability. If what Keats called negative capability refers to the power of the poet to ‘change to match their surroundings, sometimes entering fully into the psychic and sensational orbit of other beings’, then ‘any serious appreciation of Keats’ poetry begins with the section on “Private Property and Communism” from […] Marx’s Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts’. To say, then, that poetry is not work and that it lacks the direct efficacy of hauling shit in a cattle hanger is hardly to fault poetry; it is to fault an impoverished idea of what work and poetry can be.

The idea that poetry might have a special relationship to unalienated labour explicitly animates the recent writing of Astrid Lorange. In her essays, poetry, and her collaborative work with Andrew Brooks as the critical art collective Snack Syndicate, she posits and explores the possibility of a poetic form of work. Her thinking often circles back to a passage from Jordy Rosenberg’s essay ‘The Daddy Dialectic’ (2018) on ‘unthinkable’ thoughts and the fetish in Marx’s Capital. In a similar vein to Rosenberg, Lorange declares: ‘Poetry is one way to approach thoughts that are not yet thinkable’. She describes it as ‘a public labour’, the ‘ongoing and vitally necessary labour through which meaning is made—and therefore able to be remade—through language’.

It is a similar idea that drives her 2020 poem ‘Labour’. It is a poem with an explicitly feminist purpose, one that is more pointed if we recall the gendered form that labourism has taken in Australia. If work is equated with toil, then it may be difficult to credit poetry as work. But to think of work in this limited way is itself bound up with the historical occlusion of other, gendered forms of labour, such as emotional labour and care work. In the words of Lorange’s poem, this idea of work makes it difficult to recognise how:

the question of production

is also always a question of reproduction: how

the worker is made and remade daily and how

the worker is made and remade generationally

and how the worker is made and remade

structurally.

Adding further intricacy to this critique is something already noted in Morris’ Ecstasy and Economics. Morris argues, in the passage quoted above, that ‘those “new social movements” most critical of the history and practices of labourism—feminism, anti-racism, environmentalism’ have themselves been recast by the economic transformations of neoliberalism. Deindustrialization, for one thing, has been inseparable from the so-called ‘feminisation of labour’, which means, in Bernes’ summary:

not only that large numbers of women enter the workforce but that labour methods and job positions are themselves feminized. As deindustrialization displaces the characteristically male industrial worker, there are more opportunities for schoolteachers and receptionists and fewer for machinists. Furthermore, as women enter these fields (as well as fields previously barred to them), the values and affects associated with certain jobs change, and both male and female workers are asked to display attitudes and perform tasks historically coded as female.

Lorange’s ‘Labour’ is a poem written against the backdrop of these historical shifts, and it is against this backdrop that we can better understand one of the poem’s central gestures.

In defiance of the tendency of neoliberalism to draw more and more facets of life into the alienated structures of waged work, ‘Labour’ seeks a different way to enlarge the category of labour. Lorange counters the ways that capitalism reifies human activity into the wage relation by honouring the many forms of labour that these structures fail to recognise and remunerate. In other words, ‘Labour’ refuses the demarcating act that ‘marks one form of labour’ out from its ‘dizzying history’, consigning others to invisibility. Instead, Lorange declares that the ‘category of work […] must expand’:

to include the raced and sexed labour easily obscured by

economic theory; the history of labour itself – a history of

the colony, the factory, the nation-state, the city, the family,

the possession; a history of agitation, rebellion, revenge, survival,

hope, collectivity; a history of birth, death and trade; a history

of kinship, maternity and lost relations – must also be recognised

in its fulness.

The work of poetry is to think an unthinkable thought: to recognise these activities in their fullness means creating a system in which they would become unalienated forms of labour, a system in which all the many ways in which we make and remake the world would be justly shared.

The most immediate way that Lorange’s poem suggests this more capacious idea of labour is through a pun. The opening section of the poem announces itself as ‘a joke, or at least as the response to a joke: people asked “Will you write a birth poem?” or else said “Please tell me you will not write a birth poem!” […] I won’t write a birth poem, I thought, but a poem about labour’. ‘Labour’ displaces these insistent and intrusive questions into the multiplicities of paronomasia: here the word ‘labour’ means many things. Most obviously, Lorange refuses to demarcate two meanings of labour: birth and working, reproduction and production. As she explains to Amelia Dale in an interview, her poem explores:

the relation between labour—this incredible process through which a body literally passes through another—and labour more broadly, that is, labour as that which is alienated from the worker, sold on the market, and accumulated as surplus value in a capitalist economy; as well as the other kind of labour, that is unalienated, which is shared without debt (or, more precisely, as a mutual and unpayable debt), that does not accumulate but rather is transformed into meals, and conversations, and touch, and ideas, and images, and warmth, and milk, and words, and rebellions, and strikes, and revolutions.

On one level, Lorange’s poem explores the connection between different forms of labour in an analytic mode, making space in verse to deliberate on a variety of poets and theorists. Introducing Labour and Other Poems, Justin Clemens points out, for instance, how Lorange plays with Hannah Arendt’s idea of ‘natality’, or ‘the entrance of the new life into the world’. Whereas Arendt distinguishes the political power of natality from labour and work, Lorange collapses these distinctions. Labour ‘never quite finishes’, Lorange says, ‘it transforms, orients itself toward new objects. In this sense, it also never quite begins’.

Further complicating and enlivening the poem’s theoretical investigation into the connection between labour as production and labour as reproduction is the way in which labour as the work of poetic language begins to interfere with the poem’s presiding analytic register. The word ‘labour’ is used almost fifty times in Lorange’s poem, often appearing in formulations like ‘the labour of labour’, which are themselves connected by conspicuous polysyndeton (the poem’s ‘And so’ and ‘And more’). In this way, the word labour begins to function as both a charm and a riddle: repetition allows ‘labour’ to collect more and more meanings, and also causes a semantic satiation which evacuates it of those very meanings. In a charm, a pattern of sound is set up that, according to Northorp Frye, is ‘so complex and repetitive that the ordinary processes of response are short-circuited’, while a riddle is ‘essentially a charm in reverse: it represents the revolt of the intelligence against the hypnotic power of words’. In ‘Labour’, the riddle asks: how is the labour of birth like the labour of labour, and how does this connection help us to expand the category of labour itself? The answer to this riddle is much like a charm: the labour of poetry begins to associate different kinds of labour and in the process initiates ‘repetitive formulas’ that ‘break down and confuse the conscious will, hypnotize and compel’, in Frye’s words. The repetition of labour begins to surmount the reification of labour into rigid categories. It urges us to see many kinds of doing and making as labour, activities that have been invisible because they were gendered, racialised, and unwaged. Through semantic overload, the poem seeks to renew and magnify the concept of labour. This is Lorange’s way of inciting the reader to approach the unthinkable: what she calls a future ‘in which our labour is unalienated’, a poetic labouring in which value is ‘stolen back, reimagined, collectivised and embodied’.