The most remarkable event is the re-emergence of the short story as the fashionable, feted highest-paid art form. Badges and posters of Henry Lawson, Chekhov, O. Henry, Jack London are immensely popular as they become teenage idols. An international short story festival at Grenfell is called ‘Another Woodstock.’

Complex Vibrations

Thomas Moran on Moorhouse in the electronic age

In 1962 Marshall McLuhan heralded the advent of the electronic age. What did it mean for those still trafficking in print? Thomas Moran shows how McLuhan’s thinking had a decisive influence on Moorhouse’s approach to anthologies and narrative form.

The Frank Moorhouse Reading Room is an anthology of anthologies. His battered collection of Australian short fiction ranges from compilations of colonial short stories to the best of The Bulletin, historical overviews of the development of Australian prose, genre-based selections (sci-fi and crime abound), regional collections (the writing of the Gold Coast or Perth), selections of queer fiction, migrant writing, feminist stories, erotic literature, and an assortment of ‘The Best’ short fiction in Australia – choose a year, any year.

Moorhouse himself edited a number of anthologies of short fiction in his lifetime. He was a gifted practitioner of the form, but was also fascinated by the way that books, understood as technological objects, contributed to the construction of culture, history and meaning. His early fiction, which he termed ‘discontinuous narratives’, brought stories and fragments into new and explosive constellations.

‘I have quite a few possible selves’, Moorhouse once quipped. Moorhouse the anti-censorship activist is rightly well known, as is his later persona as the writer of the stately Edith Trilogy, a series of historical fictions about the League of Nations. Yet it was as a writer of short experimental fiction, and as a promoter of it in his various publishing enterprises, that he came to renown in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Moorhouse, the writer of short stories, may in turn shed light on Moorhouse, the anthologist, – and by extension Moorhouse, the media theorist, who was inspired by the work of Marshall McLuhan to question the role of literature in the electronic age.

Medium: Moorhouse, McLuhan and Printing Power

Moorhouse was precociously aware of the relationship between printing, the circulation of literature, and the history of literary form, displaying his interest in a school essay on the relationship between writing and printing. His biographer Matthew Lamb attributes this interest to Moorhouse’s family background; his father, who was the inventor of a milk preservation machine, was fascinated by the history of machinery and manufacture, and the family’s bookshelves were full of histories of this kind. Lamb also suggests that Moorhouse’s first job as a cadet journalist, in which he had first-hand experience of typesetting and layout design, provided an insight into the industrial organisation of the machinery underlying print culture.

But we might also suggest that this interest in the printing press and book history was of a piece with the era in which Moorhouse came of age. An increasing awareness of the historical power of printing was part of the intellectual atmosphere of postwar thought. S.H. Steinberg published Five Hundred Years of Printing, in England in 1955, while in France historians of the Annales School, Lucien Febvre and Henri-Jean Martin, published The Coming of the Book: The Impact of Printing 1450-1800 in 1958. These were superb scholarly studies, meticulously researched and argued, but it was the bombastic Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan whose work made a visible impression on Moorhouse’s thinking. As Lamb proposes, ‘the influence of McLuhan on Frank’s thinking cannot be overestimated.’

McLuhan is today remembered as one of the founders of media studies. ‘The medium is the message’, remains an enduring catchphrase but his wider impact on post-war culture has been somewhat forgotten. McLuhan’s reputation grew out of two books in particular, The Gutenberg Galaxy (1960), which studied the impact of print on Western culture, and Understanding Media (1964), a theory of media as ‘extensions of human perception’. Both books were read eagerly by Moorhouse and were key texts in the courses he taught in the late 1960s at the Workers Educational Association (WEA) in Sydney.

McLuhan was not only a public intellectual but a cult figure, attaining guru status as the sage of the electronic age. He appeared on television, radio, and even in Woody Allen’s Annie Hall, where he emerges out of a cinema queue to correct a movie-goer patronisingly explaining McLuhan’s theories to his date. ‘I heard what you were saying!’ says McLuhan to the man. ‘You know nothing of my work!’ McLuhan also released an album, The Medium is the Massage, in 1967, an experimental sound collage of commercial jingles, electric guitar, and excerpts of the theorist reciting passages from his own work. While McLuhan has since been critiqued for his lack of scholarly rigour and sloganeering, it was precisely these elements of stylistic experimentation and conceptual exuberance which made his work so attractive to artists, musicians, and writers of the counterculture. His work was a source of inspiration for founders of communes, organisers of happenings and pioneers of multimedia art. While Moorhouse had a somewhat fractious relationship with the counterculture, as evidenced by his satirical presentations of communes and New Age thought in Tales of Mystery and Romance (1977), his approach to writing and understanding literature in the sixties and seventies was steeped in McLuhan’s thinking.

McLuhan insisted that typography and printing radically transformed cognition and social organisation. He argued that moveable type led to the creation of the first industrially produced self-contained commodity: the book. ‘Socially, the typographic extension of man brought in nationalism, industrialism, mass markets and universal literacy’. All were made possible by print’s power of reproducibility: ‘Print presented an image of repeatable precision that inspired totally new forms of extending social energies.’ Social energies were now capable of being organised across vast distances, unifying diverse populations through the circulation of books, newspapers, and other periodicals.

This channelling of wider social energies occurred in tandem with a cognitive transformation, the birth of what McLuhan refers to as ‘typographic man’, whose mode of life is conditioned by the dominance of sight over other senses. McLuhan suggests that while mass literacy brings textuality to a wider audience, the visual-typographic thinking it encourages inaugurates a mode of ‘lineal, sequential habits’, which relegates ‘auditory and sensuous complexity to the background’. The linearity of type, as the eye scans across the page, gives rise both to the notion of historical progress and the idea of the individual for whom life is a linear movement from birth to death. According to McLuhan, this segmentation of the senses and the primacy of the eye reduce our power to draw links between diverse situations, leading to a sterile tendency toward specialisation and ultimately resulting in a ‘homogenising of experience’.

Yet for McLuhan typographic thinking had already begun to give way to new forms of aurality and orality, as the twentieth century saw the rise of radio, cinema, and television. McLuhan believed that what he referred to as the ‘electronic age’ would lead to a return of pre-typographic modes of thought while also inaugurating a new ‘iconic’ culture based on the primacy of visual emblems, symbolic affiliations and the break-down of unifying values.

While McLuhan was an astute analyst of the technologies of popular culture, many of his insights into typographic and iconic cognition were drawn from his work on modernist literature. It was the literary origins of his theory that made his work immediately applicable to thinking through literary questions; his insights lent themselves well to Moorhouse’s own project as the latter developed his short story practice throughout the sixties. Finnegans Wake is repeatedly cited in The Gutenberg Galaxy as a book that signalled a new way of writing by drawing on speech, song, cinema, and radio. Similarly, Ezra Pound’s Cantos were an abiding interest for McLuhan, and he communicated with Pound extensively between 1948 and 1957 when the poet was incarcerated at St. Elizabeth’s hospital in Washington D.C. McLuhan’s own writing adopted modernist practices of quotation, typographic experiments, and playful neologisms. It was this literary dimension of McLuhan’s media theory which gave Moorhouse a model for developing a mode of writing attuned to the new forms of sonic and visual culture that were changing Australian life in the post-war period.

Discontinuous Narratives: Literature for the Electronic Age

In ‘Something about Marshall McLuhan,’ a 1967 essay written for the WEA monthly journal, Moorhouse elaborates on the notion of media as an extension of the human senses, dryly noting that ‘presumably, plumbing is an extension of our alimentary canals’. His essay concludes by considering the effects of electronic media on what McLuhan had described as the coming ‘post-literate society’. Moorhouse notes, ‘Presumably most people will become hooked up electrically to the rest of the world – both visually and aurally – as some people and their transistors appear to be now. The post-literate society would be aural and visual.’ Given the essay’s publication in a journal devoted to adult education, Moorhouse is primarily concerned with the effect this will have on pedagogy. He notes that ‘most people who pursue adult education are typographical. Most people in society are not – they are iconic.’ Adult education will have to grapple with a future in which ‘reading and writing will be a more minority activity than it is even now’.

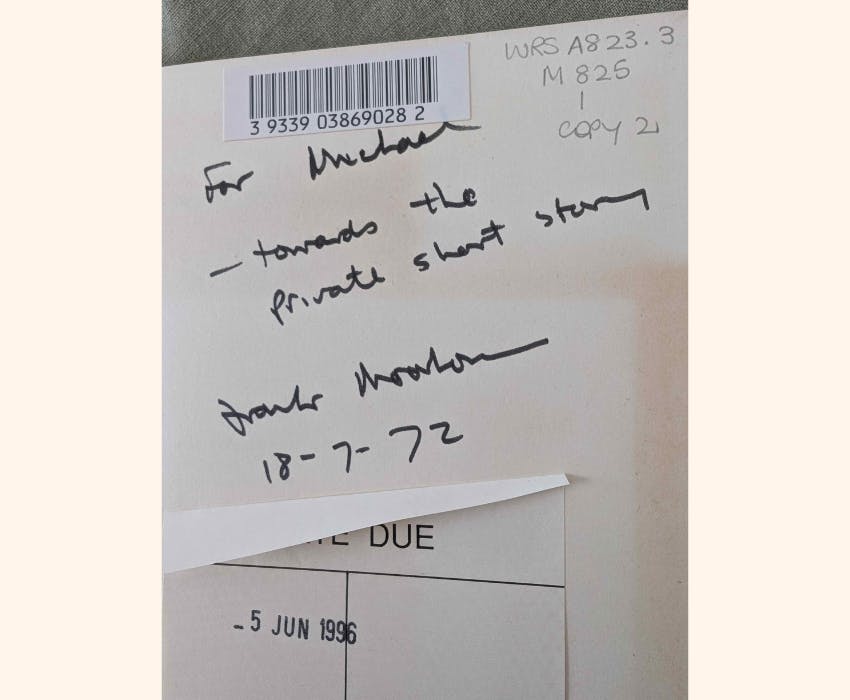

It was McLuhan’s theorisation of the end of literacy which influenced Moorhouse in reconceptualising the status of the writer and the book. Moorhouse was increasingly concerned with the effect that the end of typographic consciousness would have on writers. In a 1968 letter to his friend and collaborator Michael Wilding, he writes ‘Marshall McLuhan (groan) frightens me […] – writers as blacksmiths of this century.’ With electronic media threatening literature with obsolescence, Moorhouse wondered if the status of writers ‘as those best able to extract meaning’ was under question. He describes writing as ‘the one permanent “value” or activity worth continuing even though I am beset by doubts about my own ability and the place of literature - “the crisis of literature”’. The crisis of literature required a new form of literary production, a new mode of expression which was able to translate the electronic age into the form of the book.

In this very letter Moorhouse gave a name to his new literary form: ‘the discontinuous narrative’. He told Wilding that he had organised his short fiction into a book-length collection in which ‘the stories are all interlinked – common characters and environment – often [the] same incident from different points of view’. As Lamb suggests, this interest in discontinuity can be traced directly to Moorhouse’s study of McLuhan, who suggested that electronic culture challenged notions of continuity and linearity, traditionally ascribed to the structure of the novel. The discontinuous narrative also emerged from Moorhouse’s passion for the work of writers such as J.D. Salinger, whose characters, the Glass family, recur in a number of his books, as well as for William Faulkner’s Go Down, Moses (1942), with its seven stories linked by place, and Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg Ohio (1909). Moorhouse cites the recurrent characters in Henry Lawson’s short fiction as an Australian precedent for the discontinuous narrative, but we might also think of The Puzzleheaded Girl (1965) by Christina Stead, a book comprising four interconnected novellas, as another precursor.

The publication of his first book Futility and Other Animals in 1969 included Moorhouse’s explanation of the form: ‘These are interlinked stories and although the narrative is discontinuous there is no single plot’. In his third-person author bio he extends this idea, noting that ‘He writes short stories and does not intend to write a conventional novel.’ When he was negotiating the publication of The Americans, Baby (1972), he demanded that the publisher not advertise his book as a collection of short stories. The Americans contains a series of notes to guide the reader to other places where the characters have already appeared. ‘For readers who would like to know more of Cindy, the girl in “The Story of Nature”, I refer them to […] Futility and Other Animals.’ In The Americans characters like Becker, the Coca-Cola salesmen, and Johnson, an American reporter, appear in a number of stories, sometimes as protagonist and at other times in the background of another character’s experiences.

Some contemporary reviewers of these books were unconvinced by the experimental structure. Brian Kiernan, reviewing Futility for The Australian, argued that ‘the experimental form does not make the collection a unity.’ Marion Halligan had a similar response to The Americans, Baby, suggesting that the stories had ‘neither the fullness of characters in a novel nor the brief completeness of characters in a short story’. Most reviewers focused on the transgressive sexuality portrayed in the books, the frequent use of ‘coarse language’ and the way they challenged the regime of censorship.

But as Moorhouse persisted with the form and his reputation grew, more astute critics noted that literary discontinuity could be read as a reflection of the discontinuity of modernity. Reflecting on Australian short fiction in 1984, novelist and critic Nicholas Jose suggested that Moorhouse’s ‘discontinuous narratives piece together discontinuous lives’. For Jose, discontinuity was a distinctly Australian structure of feeling: ‘fragmentariness suits the confusion and incompleteness of identity many Australians feel.’ Don Anderson, a writer and friend of Moorhouse’s, did not think discontinuity was a specifically Australian sensation, arguing that Moorhouse should be seen as part of a wider movement in experimental fiction that encompassed American writers like Donald Barthelme and John Barth. By linking Moorhouse to the American ‘Black Humourists’, Anderson makes an important point: while Moorhouse was often seen as more of a quotidian realist than his contemporaries Peter Carey and Murray Bail, the overarching structure of his books and his refusal of the closure of individual stories within a collection make his work far more avant-garde than many had realised.

However, what is missing from much of this speculation was the role that technologies, including the technologies of printing, cinema, and radio, had on Moorhouse’s writing. For the Moorhouse of the sixties and seventies, the so-called ‘conventional novel’ could not address the discontinuous character of technological modernity. This intertwining of writing and technology was designed not only to replicate the anomie or chaos of the age, but to create a form attuned to echoes, resonances and curious intersections. In an interview with Candida Baker from 1988, Moorhouse explicitly described the discontinuous narrative as a technological form. Adopting the language of computing he said, ‘I see it as circuitry, circuits within the larger assembly, with the books coming in, one in another.’ The discontinuous narrative generates a kind of fragmentation which produces unexpected connections – not only between the stories in a single volume but across Moorhouse’s entire oeuvre.

In Moorhouse’s work not only characters but entire stories reappear, with ‘The St. Louis Rotary Convention 1923, Recalled’ printed in both The Americans, Baby and The Electrical Experience (1974). The role of the reader in this fractal structure is to notice these resonances, to recollect a character or situation (that might itself also be a recollection). When asked if he would ever consider writing a novel, Moorhouse said, ‘No, although the paradox might be that all my work is a unity’, suggesting that an ultimate will-to-unity pervades what otherwise appear to be jagged fragmentary texts.

Moorhouse’s interest in the discontinuous narrative as a technological form reaches its apotheosis in The Electrical Experience. The book follows the travails of George T. McDowell, a manufacturer of soft drinks and a keen Rotarian, and his milieu. It was originally conceived as a technological history of the South Coast of New South Wales, where Moorhouse grew up. Unlike his earlier books that focused squarely on the present, The Electrical Experience contains stories set in the 1920s and 1930s, tracking the effects of the telegraph, the motor car, refrigeration, and agricultural industrialisation on rural life. This book is Moorhouse’s most ambitious experiment with the book as an object, with different forms of typography denoting different eras and the inclusion of double-page archival photographs of inventions and advertisements. Interspersed throughout the volume are black pages with white text. These blocs of darkness interrupt the stories with small fragments including jokes, excerpts from real and invented newspaper articles, lists of extinct idiomatic expressions and instructions for making a ‘home cooling system’. Wearing its discontinuities on its sleeve, The Electrical Experience radically embraced the technical possibilities of print, typography, and image in book form.

Short Story: Tabloid Story and the Coast to Coast Anthology

Almost all the stories that appeared in Moorhouse’s discontinuous narratives had originally been published as standalone pieces in magazines and newspapers or entered in competitions. While Moorhouse considered the short story suited to the aesthetic paradigm of the electronic era, finding an outlet for publication was difficult. Consequently, Moorhouse and other young writers throughout the 1960s turned to publishing in what were then termed ‘girlie magazines’.

As part of his regular column for The Bulletin in 1972, Moorhouse satirically prophesied – along with the collapse of censorship, women and gay liberation, and ‘an eventual disbanding of the parties as we know them’ – the renaissance of short fiction:

Moorhouse did his best to inaugurate the age of the short story in 1972 by starting the magazine Tabloid Story with Wilding and Carmel Kelly. Described as a ‘travelling exhibit for the short story’, Tabloid Story was conceived as a supplement that could be ‘hosted’ by existing newspapers and magazines, like Nation Review and The Bulletin. In part it was a reaction to what the editors believed was the formal conservatism of Australian literary journals like Overland and Meanjin, the limits placed on writers by official censorship, and the difficulty of receiving payment from newspapers. (Moorhouse had once arm-wrestled Gareth Powell, the editor of Chance magazine, for a cheque.) Tabloid Story was the first Australian magazine to advertise its rates of pay and insisted on remuneration for its authors.

In seeking to mediate between the underground press and the more established print culture in Australia in the early seventies, the Tabloid Story project can be understood as an extension of Moorhouse’s interest in media theory. By reorganising the circuits of distribution (where short stories were read and how they circulated), Moorhouse, Wilding, and Kelly sought to reorganise practices of writing and reading, from both an industrial and a stylistic vantage point. Tabloid Story was intended as a catalyst for experimental short fiction in Australia, and part of a larger push back against what Patrick White had famously called ‘the dun coloured journalistic realism’ of Australian fiction.

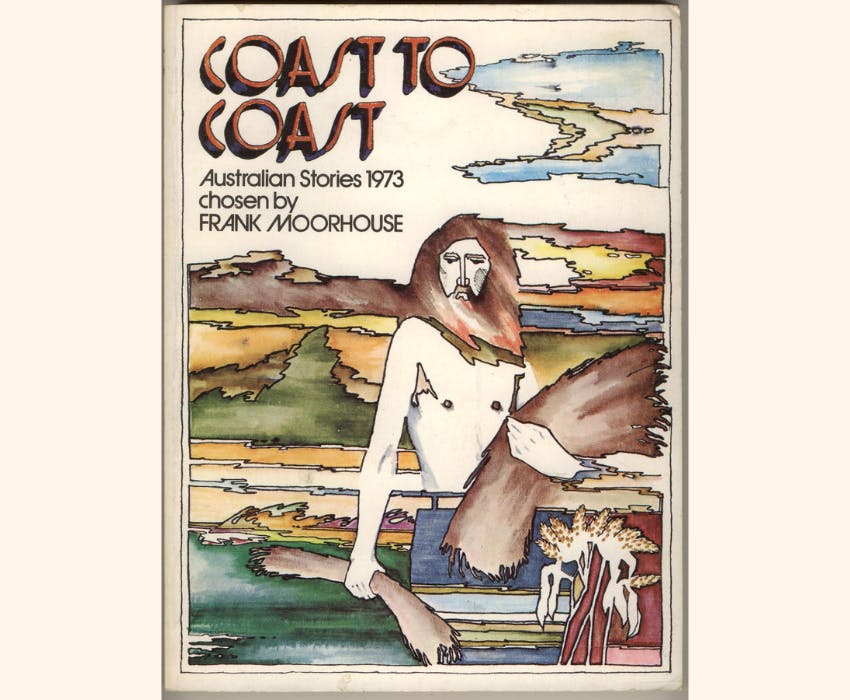

It is in this context, of the opening up of new circuits and formal possibilities for short fiction, that we should read the first anthology which Moorhouse edited, the 1973 edition of Coast to Coast. Published by Angus & Robertson, Coast to Coast had begun in 1941 and was an annual, sometimes biannual, series which showcased ‘the best’ writing of the year. Each volume was edited by a different Australian author: left-wing realists like Frank Dalby Davison (1943), Vance Palmer (1944), Nettie Palmer (1949-50) and M. Barnard Eldershaw (1956), to Hal Porter (1961-62) and, finally, Thea Astley (1969-70). The series was initiated by Beatrice Deloitte Davis, Australia’s first full-time editor, employed by Angus & Robertson since 1937.

In 1973 Coast to Coast had been out of action for two years and the decision to choose Moorhouse as editor was a purposeful one. He was picked by Richard Walsh, the former editor of controversial counter-culture magazine Oz and the new head of Angus & Robertson (his appointment an indication of the cross currents between the different strata of the media that Tabloid Story had tried to exploit). Moorhouse as anthologist was a contentious decision: Davis actively disliked his work and had been opposed to Angus & Robertson’s publishing The Americans, Baby the year before. By placing Moorhouse, the enfant terrible of Australian letters, at the helm of Coast to Coast, the publishers hoped to bring the series into a new era.

The design of the 1973 edition of Coast to Coast (preserved in the Frank Moorhouse Reading Room) announces a rupture. Earlier editions were book-sized, B or C format; Frank’s is larger, more a magazine than a book. The cover: an image of a bearded hippy, not unlike Jesus, emerging from a psychedelic landscape a bushel of wheat in his arms. It’s the kind of graphic design that might have appeared on a folk-rock record or surfing magazine of the time. The inner sleeve is the earthy brown tone of Epsomware, the seventies Australian stoneware produced by Bendigo pottery. Each story is accompanied by a large (sometimes full-page) photograph of the author, drinking, smoking, or staring moodily at the reader. Moorhouse is photographed atop a car, a tinny in his hand, posing jauntily for the camera.

Moorhouse’s editorial introduction carries on in this irreverent spirit: ‘I have never been accepted for Coast to Coast – except by myself. This was one of the reasons I took the editorship.’ It acknowledges the change in editorial direction signalled by his appointment:

The editor of Coast to Coast is usually secure in the tradition and secure in status. The early publicity […] sponsored anxiety because of talk about [a] new approach and new styles and ‘breaking with tradition’. The anxiety was that this volume of Coast to Coast would be some cruel sorting-out of writers into those who were passe and those who were O.K. (presumably those who smoked pot).

He notes that his selection is not so much representative of everything or everyone as ‘personal – I-like-it-I-Iike-it-not-test.’ While he writes that it would be ‘unsettling and unreal’ if the stories did not contain references to drugs, Vietnam and ‘liberationist concerns’, his criteria for selection he insists is formal: ‘I was […] interested in not only what was being written but how it was being written.’

The selection of writers includes many names historically associated with Moorhouse and his generation – Bail, Carey, Wilding, Carmel Kelly and Vicki Viidikas all appear. But older writers like Hal Porter, Christina Stead, Dal Stivens, and Dorothy Hewett are also represented. There are writers staring out from black and white photographs who seem to have disappeared completely from history, men with brooding expressions and long unkempt hair, women holding children, a country schoolteacher surrounded by her pupils, an author identified only by hand-drawn yin-yang symbols. An excerpt from The Cream Machine, a forgotten novel by Vietnam veteran Rhys Pollard (‘at the moment preparing for an engine driver’s exam with the Victorian railways’), recounts ‘the scything satanic chaos’ of an ambush. Social worker Helen Pavlin’s ‘With Leaf-like Ear’, subtitled ‘Lines written in a women’s college’, describes the tentative and tender longing between the narrator and an unnamed woman. ‘Acid Man’ by Peter Loftus documents an acid trip in which the protagonist envisions ‘an exiled jeweller from Bohemia hired at a taxable rate’ to design bathplugs.

For the first time in Coast to Coast, the collection featured non-fiction. Moorhouse’s introduction reflects on the importance of publications like Thor, the surf magazine Tracks and the anti-establishment Sunday paper Nation Review – all sources of what he describes as ‘imaginative journalism’, or what was often termed ‘New Journalism’. John Witzig interviews the young surfer Mark Warren, on pot, pottery, and his dad’s honey (‘it’s unreal honey […] I’ll get you some if you like’). A piece by humourist Ross Campbell, ‘Ozification Program’, playfully riffs on Walsh’s appointment and ‘the creation of a new, swinging Angus and Robertson’ by adding obscenities – signalled by fill-in-the-blank underlines – to the bush ballads of Banjo Paterson. The anthology thus helps map the changing landscape of Australian publishing. This sociological aspect was not lost on Moorhouse, whose editorial explicitly notes the connection between the media structure and the form of the short story.

Eschewing editorial politesse (‘in looking at the stories submitted, and the stories published in the last two years I did not find an abundance of riches’), Moorhouse concludes his editorial by refusing ‘a statement of faith about the future of the short story’. Instead he turns to the question of the possible obsolescence of the form, invoking the crisis of literature which inspired his turn to discontinuous narratives: ‘There is no virtue in an unwanted craft, and as popular entrainment the short story is almost dead.’ Yet even in this unconventional introduction, Moorhouse cannot help but advocate for the form: ‘It seems to me that the short story is a natural form, akin to the dream, the oral tale and the fantasy.’ This manner of understanding the short story, as an offshoot of the tale or ‘yarn’, had been part of the discourse of The Bulletin in the nineteenth century, linking short story writing to oral settler culture and the kind of national mythos that writers like Bail had begun to deconstruct – via Russell Drysdale and Lawson – in stories like ‘The Drover’s Wife’ (1975).

Moorhouse is far more penetrating when he turns to the question of technology. The short story ‘has all the standard technological advantages of the printed word (comparatively unrestricted distribution, can simulate all the senses, is easily retrieved, is portable, can be consumed at a personal pace)’. This is language steeped in McLuhanism. Yet Moorhouse also expands his analysis to suggest that the short story has ‘special advantages’ in its medium-agnosticism: ‘It can be specialised subculturally and regionally and, unlike the novel, it can be published outside book form.’ It can also be performed live; a number of the stories are introduced as having been heard first at a reading. Moorhouse was one of the organisers of the ‘Balmain Poetry and Prose Readings’ which were a lightning-rod for Sydney writers in the 1960s and early 1970s.

Short fiction in the sixties and seventies was plugged into contemporary circuits of performance, political protest, and collective actions. The capacity of short stories to be performed made them not only typographic but part of the new aurality and orality that defined the electronic age. Since recording and reproduction are dialectically entwined with performance and ‘liveness’, short fiction also featured on radio programs in that era as part of both the ABC’s programming and community radio stations. Given its technical advantages, the short story, wrote Moorhouse, ‘can be an intense form which releases complex vibrations, not readily reducible to simple political or moral analysis. I can’t see why it shouldn’t continue.’

Coast to Coast would not continue, although it was briefly revived in 1986. Nonetheless, as Moorhouse’s reputation in the world of Australian letters grew, he was asked to edit more anthologies, including the sparkling collection State of the Art (1983), which showcased the next generation of writers, including Jose, Helen Garner and Beverley Farmer. Yet there remains something particularly arresting about the 1973 anthology, a utopian power which speaks not only to the spirit of that moment in Australian history, but also to the capacity for the anthology to function as a complex literary object. There is an attractive insouciance and anti-institutional bravura which courses through everything from the design to the writing itself – proof of Moorhouse’s insistence that the short story has unique formal possibilities. In his hands, the anthology, like the discontinuous narrative, becomes a mercurial piece of technology, releasing ‘complex vibrations’ between the most intimate phrase and an increasingly intricate media network.

The pressure of the ‘electronic age’ on literature has only intensified since Moorhouse developed the discontinuous narrative. While digital technology is powered by algorithmic calculation and a material infrastructure of minerals, server farms, and pipelines, it is experienced by most users as a narrative machine, in which sound, video, image, and text flash by at ever-quickening rates across our screens. Literature is inescapably installed within these circuits, shaped by the perceptual and cognitive effects of media forms.

On the one hand, the popularity of ‘flash fiction’ suggests the reduction of narrative to a microscopic minimum, while, on the other hand, multi-volume sagas within genre fiction emphasise immersive world-building and descriptive detail. Both of these phenomena can be understood as narrative responses to digital networks as writing morphs to the rhythm of the feed. Yet neither form really captures the strange temporality of digital life. Perhaps the discontinuous narrative and the kind of uncompromising formal experimentation that Moorhouse extolled present paths we haven’t yet exhausted. At the very least, it is necessary to maintain a hold on the dialectical tension which Moorhouse found in narrative discontinuity – a mimetic echo of the flux of a disjunctive age in which all that was solid was rapidly melting into air, and, simultaneously, a mode of generating connection between bodies, technology, and ideas – if only for the time it takes to read one of his collections.