Walter Benjamin, ‘Imagination’, in Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings vol. 1, 1913-1926, ed. Marcus Bullock and Michael W. Jennings (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004)

Walter Benjamin, ‘The Author as Producer’, in Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings Vol 2, Part 2, 1931-1934, ed. Michael W. Jennings, Howard Eiland, and Gary Smith (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005)

John Berger, ‘Art and Property Now’, in Landscapes: John Berger on Art (Verso Books, 2016)

Silverfish, Weevil, Ibis

Astrid Lorange and Andrew Brooks on Simryn Gill

We unfurl the pages of Clearing one by one, join them together to reveal a continuity of lines and smudges, a spectrum of markings from nebulous and indistinct to precise and definite. A Canary Island Date Palm with the roots of a Moreton Bay Fig has been made to appear on the carpeted floor outside a row of offices in Block F of UNSW Art and Design. This site underwent its own clearing in the mid-2010s to make way for a generic university campus, and in the process disappeared the ramshackle ecology that the combination of green space and run-down buildings enabled; or as our friend puts it, the pre-clearing version featured: ‘an enclosed leafy courtyard, intimate little spaces, a maze of corridors and ramps; conversations happening on multiple levels, people talking up and down; no main entry (so the campus always felt private and safe); trees and therefore shade; a great cafe in the centre; and lots of smoking.’

To be more precise, it is a spectre of the palm that has appeared before us, the trace of a once muscular tree rendered a two-dimensional relic. As we line the sheets up and down the corridor, we straddle and squat, facing the army barracks that sit adjacent to the campus. The barracks, we remember, feature a tall line of date palms that separate the small car park from the regency-style architecture – perverse, Ovidian guards. Date palms appear as ubiquitous witnesses to the settlement of this land, these Countries, carrying with them the evidence of invasion as structure, infrastructure, logistics, and bureaucracy.

Simryn Gill, Clearing (detail).

We stack the pages again, fragmenting the tree back into discrete sections in order to attend to what is printed on the recto. Or are we looking now at the verso? As we turn the pages, following the relations the tree implies, a small cockroach runs circuits between our legs. We follow the patterns charted by the much maligned roach, thinking now of the big ones that stroll, on a hot summer night, into the terrace house we live in on Wangal land, through the sizable gap of the heavy wooden front door that supposedly marks the boundary between inside and out. From our habitual vantage point of the couch or a pillow on the floor, the roaches run shapes beyond our comprehension, remapping the familiar space according to supply lines and nesting spots invisible to us. If we remember to look, things are never exactly as they seem. Follow the roach or the date palm into history and it will lead you to the imaginary. Or study an image of the constellations of tiny holes left by silverfish on the pages of old books belonging to Simryn Gill and you will discover these words by the seventeenth-century French poet and theologian François de Salignac de la Mothe-Fénelon: ‘But let us supplement by means of imagination what our vision lacks, and let our imagination itself become a kind of microscope that shows us in each atom a thousand new and invisible worlds: even it would not be able to show us in the little bodies new discoveries with limit: it would too exhaust itself and be forced to stop, to succumb, and to allow a thousand wonders to remain unknown in the smallest of bodies.’

Simryn Gill, Clearing (detail)

Our daughter brought home from preschool a contraption she’d made with some old cereal boxes and cellophane. A large body and a perpendicular arm that appeared as a two-headed telescope. It’s a machine, she said, for filming Planet Earth. It can go closer than the cameras they use now. Last week we introduced her to the BBC television show, a documentary shot with uncanny lenses to reveal rare animals in their degraded habitats. After the first episode she had asked if it was ‘real life’, confused by the simulated intimacy afforded by cameras suited to capturing far away celestial bodies. It is, we answered, but it is a vision of real life that is also an illusion. It was hard to explain how fraught this documentary vision is, how her ambivalence about it was shared by us even though we know its trick in advance. It is hard to know what to do with images that are not quite ours to see; hard to know what to do with the feelings that the images arouse in us. The universe of the creature, we might say, does not belong to us, though it is inseparable from our own in ways that are painfully, ruinously uneven. But our daughter’s rudimentary machine, inspired by her ambivalent encounter with a mode of visual capture at once real and illusory, brought something novel into view – a way of seeing attuned to the dynamic relation between the material world and imagination. Her machine is a tool to help those of us whose thinking has been disciplined by disciplines to perceive the relationality and ephemerality of a world in constant transition. We watch our daughter venture into our back garden where she crouches beneath the overgrown passionfruit vine, nestles in beside the curry tree and chats to the tiny spiders who weave delicate, almost invisible webs between the ferns and yet another type of palm – the areca – which is well suited to indoor spaces and shady suburban enclaves. She invites the spiders to crawl over her hand, loses herself in their worlds before rushing over to report on the constantly shifting architectures they construct. Imagination, Walter Benjamin once wrote, ‘has nothing to do with forms or formations’ but rather is ‘the deformation of what has been formed.’ Benjamin’s imagination is grounded in all of the complexity of the material world – environments, histories, social relations – which exist in a state of perpetual movement; dissolution extending toward transformation. Deformation, he writes, shows us ‘the world caught up in the process of unending dissolution; and this means eternal ephemerality.’ Our daughter’s machine – cereal box, cellophane, masking tape – seemed to suggest a way of looking that follows the relations from the material realm into the imaginative one. Simryn Gill’s Clearing does this too: inside the rubbed cross section of the trunk of a date palm we find a series of solar flares, in the grain of paperbark we feel the movement of the tides, in a network of roots we find the tentacles of a giant squid.

Simryn Gill, Clearing (detail).

But perhaps we have followed Gill’s lead, and wandered off the point. We began somewhere in the midst of things, tugged at one of the tangled threads and found ourselves following it out of, and back into, this strange book. The book in question, as you will have gleaned, is called Clearing by the artist Simryn Gill and published by Stolon Press and the Art Gallery of New South Wales. But to call it a book is somewhat misleading, a more accurate description might be a folio composed of a series of unbound leaves that invite the reader to touch, lift, turn, and recombine. This description does not suffice either: the word folio suggests an object more definite and ordered and precious than the one in front of us.

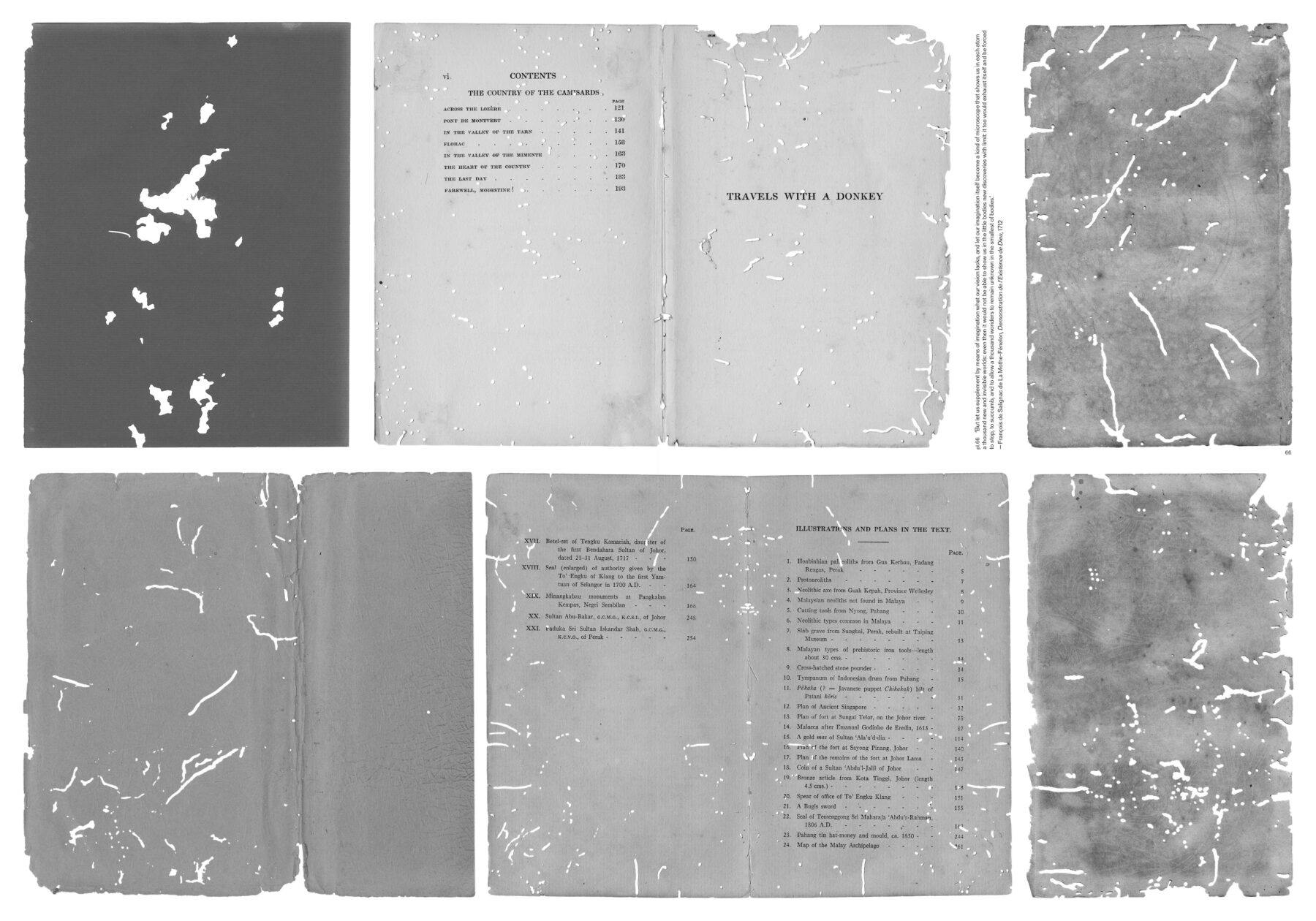

This object might best be thought of as an ecology, a network of living, changing relations. We woke up early the other morning to read a little before the day became dominated by the rhythms of work. Our cat hurried into the front room, punctuating the silence with a series of yells that seemed to announce his surprise at finding us awake at this hour, and then stretched out on the firm yet inviting pages of the object in question. These pages invite use, suggest inhabitation, become part of the fabric of the house. Across the pages, there is a long essay by Gill that tells the story of the artwork Clearing, commissioned by the gallery as part of the redevelopment of its site to include a new ‘campus’. Gill’s response to the invitation was to plan a large scale ‘rubbing’ of the enormous palm temporarily uprooted to make way for construction – such experimental and vegetal forms of publishing are part of Gill’s practice and suggestive of a long term engagement with the tree as an object of study and collaborative partner. When the relocation was scrapped because the tree had been found to be infested with lesser coconut weevils and therefore unsafe for further planting for fear of contagion, Gill’s rubbing took on a new meaning: it became a kind of elegy for a condemned tree, a record of dispossession, displacement, and disposability unwittingly indexed in the tall, honeycombed body of a palm undone by tiny parasites. The story of Clearing is told by Gill in a way that suggests the impossible fullness it indexes: nothing short of the entire world is collected by a story that can be traced through the history of empire, conquest, rebellion, and survival. And so it is that Gill’s story is expansive, proliferative, endlessly energetic, hungry for those moments of convergence and encounter that give life meaning and lend study its necessary coordinates. Alongside the essay are images that correspond to Gill’s writing and offer departures from it: some are archival images, some found, some taken. All of the images are accompanied by captions written by Tom Melick: essays and poems in their own right as well as snippets of historical and literary texts that comprise a rich bibliography. On the reverse side of the pages that interleave text and image, there is a modular reproduction of the rubbing itself, composited with an earlier work that took the long, tangled roots of a Moreton Bay Fig from the same site as the object of gentle frottage. Then, there is an ‘insert’, a pamphlet containing the essay ‘A tree is a tree is a tree is a tree’ by Catherine de Zegher. This essay situates Gill’s work alongside her practice more broadly, as well as offers a history of the tree in art and philosophy. To speak of this unruly object, then, requires acknowledgement that we are speaking of something always in excess of the descriptions that would seek to contain it: we are speaking of something that, no matter which way it is approached – left to right, front to back, big to small, image to text; author, editor, collaborator – is alive. To read it, you need the tenacity of a lesser coconut weevil, munching arcades through the heart of a palm.

Simryn Gill, Clearing (detail).

What of the lesser coconut weevil? Lesser than what? To evoke Jakob von Uexkhüll, as he is evoked throughout the different texts that comprise this folio, we might blow an imaginary bubble around the universe that the weevil inhabits: an impressive world for a small insect who nonetheless can burrow through an enormous centenarian palm, can chew intricate lacework from its soft interior. A scientific paper calls the habits of this weevil ‘cryptic’, which we might take to mean at least two things: its presence is belatedly marked on the exterior of the tree through subtle codes of colour and pattern; and it makes the tree into its own grave. Another factsheet outlines ad hoc methods of trapping the weevil in its horny pursuit of endless eating and fucking. You can, it says, lay a trap in the form of a bucket filled with sugarcane. This device has something to do with pheromones, and lures the insects to their death. Sex, syrup, palm heart: the weevil’s life is easily reduced to a problem for pesticidal correction but on second look it has the trappings of a sumptuous, decadent orgy. Such details do not escape Gill’s curiosity, nor we might say, her solidarity. Just as she feels a creaturely affinity with the silverfish who run libraries’ worth of books through their tiny guts, she feels an affection towards the weevils whose universe is unwittingly the pivot point in which the epic story of a palm’s relocation for the sake of art turns into a tragedy. The palm must die because its contingent life on this hill, its passage from the Atlantic to the new colony by way of the metropole, has carried with it the coincidence – even inevitability – of it coming face to face with a parasite also displaced and adrift southwards. Gill’s rubbings reveal the curious glyphs written by the weevils, as it also reconstructs the other creatures who find their own universe in the Canary Date Palm: chiefly, the rat and the ibis.

These creatures offer a way into the folio, a way to read the manifold relations. The sheets can remain folded, to reveal one larger, unbound book and its smaller companion, bound by a single piece of white thread. The sheets can be unfolded, made into an articulated poster, a miniature artwork, a hybrid of date palm and fig tree. In book form, the pages can be read in order, following images and their captions, columns of text, colophon and body. Or we might read by creature: follow silverfish, or ibis, or weevil, or squid, or camel, or rat. We might read Tom Melick’s bibliophilic captions as a study guide for an expanded, life-long version of this publication. We might read one of the tributaries that runs off from the central current of Gill’s text and therefore dwell for a while in a single word, poem, slice of bread, wisp of hair or paperbark sheaf. We might read into the inherent partiality of origin stories, treading a path between apocryphal tales, ancient knowledge, settler anxiety, and the desperate attempt to formalise the ephemeral. Or we might read the texture of the images, attending to the humble yet precise quality of the photocopy. The refusal of glossy images in favour of simple reproductions draws our attention to the apparatus of production: the photocopier, a reliable machine of mass duplication.

To read the book as a collection of black and white photocopies is to read a commitment to experimentation with the materials and tools of everyday communication – machine, paper, ink, object, hand. More than this, it is to be reminded that books can be indexes of living processes, necessarily incomplete offerings that open out towards the reader rather than fix a certain idea of itself in place and time in the manner of a relic or what John Berger would call a ‘ritual object’ of art. The photocopier is central to Stolon Press, a publishing project that emerges from friendship, conversation, community, and solidarity and that is avidly dedicated to the publication of those things that, as our friends describe it, ‘might easily fall through cracks or remain in boxes and bottom drawers.’ In her acknowledgements to this book, Gill points out that, despite the institutional support given to this project, Clearing ‘is a Stolon Press book in more than just name.’ She continues: ‘we proceeded with the same unfiguring, unlearning and unhoning that our black and white photocopier demands from us.’ To read Clearing is to encounter an undoing that is always generative, opening us up to new relations and invisible worlds. In it, we find a mode of production that encourages further production outside of the abstract reification of ideas and objects. To hold this book, to assemble and disassemble it, to follow the threads that lead us away from it and back into it, is to apprehend a mode of authorship and publishing concerned not simply with the making of this text or that but with enabling the sharing of ideas, relations, and worlds. Such an approach takes publishing to be a collective act that, as Walter Benjamin called for almost a hundred years ago, has the capacity to ‘induce other producers to produce.’ For Benjamin, the task of the author was not simply to produce content, which too-easily becomes trapped within the circuits of commodity production, but to create an apparatus that suggests the transformation of production itself. ‘And this apparatus is better,’ wrote Benjamin, ‘the more consumers it is able to turn into producers – that is, readers or spectators into collaborators.’ Clearing makes a collaborator of each of its readers, inviting us into the discarded remnants found in the colony and out toward the creation of worlds yet to come.