I, Was, Am?

Nina Culley on zombies and what identity looks like when it’s stripped away

What remains of the self when familiar markers of identity – names, physical traits, personal histories – are lost? Nina Culley considers what answers Anne de Marcken’s latest novel has to offer via its zombie narrator’s perspective.

I know that I am me – that these are my hands, that this is my laptop. I know that I like my noodles packaged and pre-seasoned, and that I am a writer, etc., etc. This is my amateur attempt at playing with the elusive ‘I’, by which I mean not just the grammatical first-person pronoun, but ‘I’ in the broader, conceptual sense, as a representation of selfhood or identity.

In fiction, the ‘I’ is meant to be identifiable, tethered to tangible characteristics: F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Nick Carraway, in The Great Gatsby, is an outsider; he’s composed, honest, and relatively passive (or that’s what he wants us to think). Suzanne Collins’ Katniss Everdeen is fiercely independent, moral, and great with a bow and arrow. She usually wears her hair in a single braid and was born in District 12. We’re generally accustomed to understanding characters like these through a familiar lexicon of traits or constructs, where they are, for better or worse, tied to their settings, attributes, and goals, like a marionette to its strings. But what happens when the strings are cut? When a character is deliberately unmoored from their body, their past, their self? I found myself asking this over and over while reading Anne de Marcken’s experimental novel, It Lasts Forever and Then It’s Over.

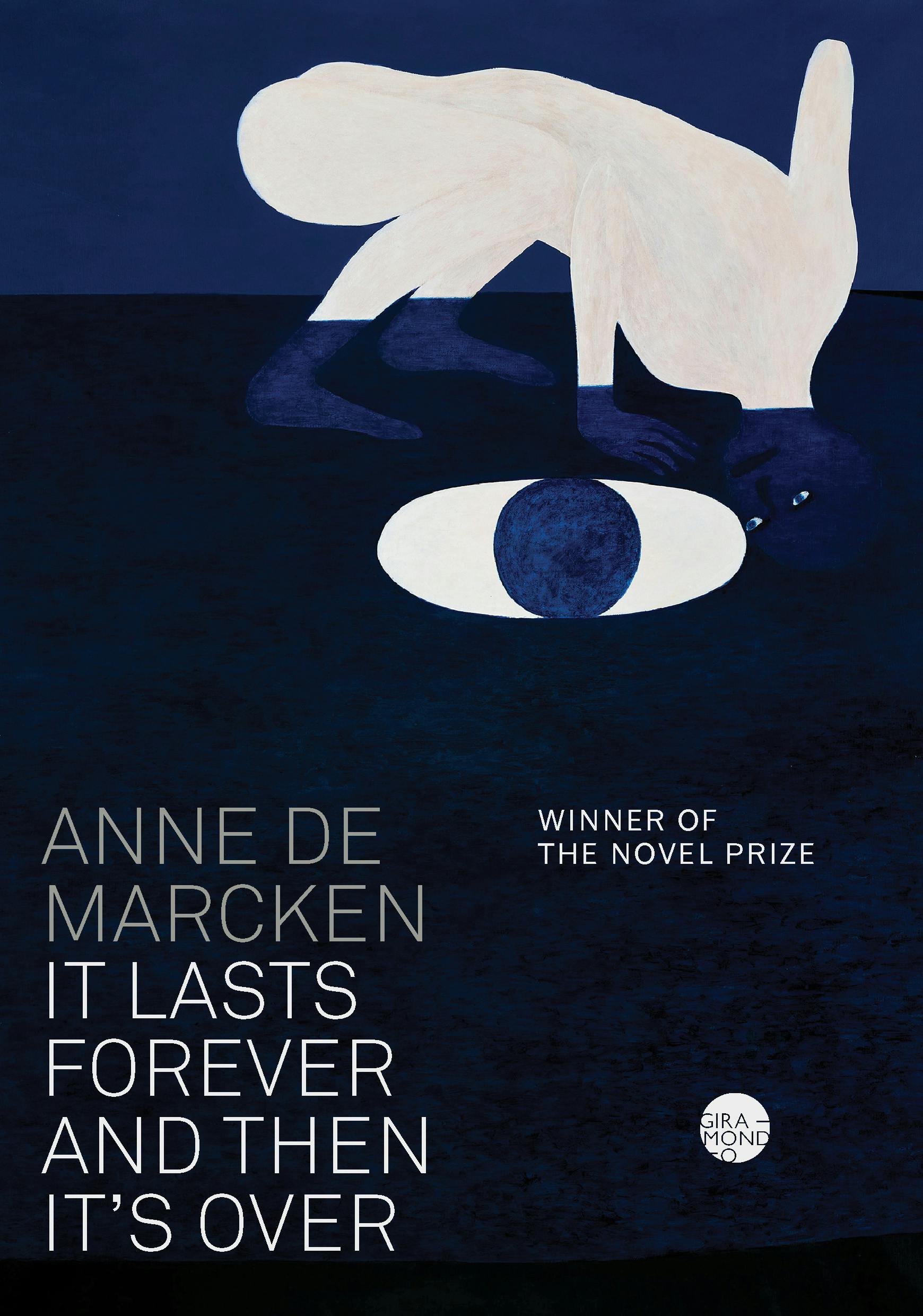

This isn’t de Marcken’s first foray into experimental fiction. In 2019, she published The Accident, a story about loss and impermanence that disrupted traditional narrative conventions with its images, QR codes, and deliberate textual fragmentation. Similarly rebellious, It Lasts Forever and Then It’s Over deploys stylistic choices that favour abstraction and poetry over plot. Sectioned into seven short parts – each bookended with epigraphs from literary figures such as Fernando Pessoa and Hélène Cixous – the novel’s prose is rhythmic and meditative. Three illustrations punctuate the text: a dashed line, an ‘unruly’ spiral, and an axonometric cube – drawings de Marcken says she created herself to help conceptualise the novel’s shape.

To me, the most strikingly experimental element of the book is its treatment of identity. To start with, the protagonist introduces herself by the very thing she’s missing. The opening hook is: ‘I lost my left arm today’. From there we learn that she also lacks key markers of identity, remembering nothing about her former life – not her name, her hometown, or even her favourite ice cream flavour. ‘I am worried that I am getting other guests’ stories mixed up with my own. Did I like strawberry ice cream? Did I grow a zucchini the size of Ed’s leg? Did I have a green toy truck?’ she wonders early on. Trapped in her perspective, and unsure of what’s true, we rely on her unreliable narration, piecing together her identity from a patchwork of possibly borrowed memories and half-remembered stories. Her sense of self isn’t stable – it’s circumstantial, malleable. There’s reason for this, of course: it’s because she’s a zombie.

As a fan of the zombie genre, and horror more broadly, I adore how de Marcken leans into its familiar tropes. Naturally she includes an eerie, deserted landscape – overgrown parks, endless roads, empty truck stops, forgotten Starbucks cafes and minimarts – typical of human survival stories like The Walking Dead or games like The Last of Us. The zombies themselves – including the protagonist – resemble the classic archetypes made famous by George A. Romero: slow, groaning, perpetually hungry, sad.

But in other ways, they resemble those in Isaac Marion’s zombie-romance Warm Bodies. Like Marion’s protagonist, de Marcken’s lead zombie is self-aware, existential, and able to experience ‘human’ emotions. Both narratives are told in the first person, both lean into a kind of black comedy – a fitting and welcome by-product of the zombie subgenre. Marion’s protagonist, for example, muses, ‘What does it mean that my past is a fog but my present is brilliant, bursting with sound and colour? [...] I can recall every hour of the last few days in vivid detail, and the thought of losing a single one horrifies me.’ This could almost belong in de Marcken’s novel. In both cases, the zombie isn’t simply struggling to survive – it’s trying to remember, to recover something lost through a kind of metaphysical or abstract consciousness.

Of course, Romero didn’t invent the zombie from scratch. He drew on older traditions – particularly Haitian Vodou, where beliefs about zombies developed associations with the horrors of slavery and colonialism. Since then, the zombie has become a flexible metaphor: for capitalism, apocalypse, loneliness, labour. In Ling Ma’s Severance, the ‘fevered’ become symbolic proxies for those enslaved to the numbing monotony of late-capitalist routine. Meanwhile, Max Brooks’ World War Z interrogates government control, war, and the complexities of being human. In the same vein, de Marcken uses the zombie as both metaphor and mechanism, exploring loss and what it is like to inhabit the space between life and death.

She even begins the novel in that space: a hotel – a literal holding place for travellers suspended between destinations. Buddhists, myself included, might call this an ‘in-between space’, or ‘bardo’: a transitional state between life and death, or even between thought and action. As the story unfolds, the hotel morphs into something stranger – a post-apocalyptic purgatory reflective of the characters’ liminality. This is where surreal elements begin to accumulate: a moon that remains full until the book’s end, blinking fireflies that punctuate the stillness. These details suggest there’s an uncanny dream logic at work in this world, where the setting may look like real life but operates just a little off-kilter. For readers this becomes a space that is both recognisable and alien, much like the narrator’s state of being.

At the hotel, the protagonist meets Janices 1, 2, and 3 (though she’s closest to Janice 2), as well as Marguerite and Mitchem, fellow zombies who also retain no memory of who they once were. The loss of names becomes one of the novel’s first instances of loss. Stripped of this basic symbol of identity, the characters are compelled to rename themselves. They scrawl names on dust, on walls, on air conditioning units. But dust is impermanent – each name will vanish.

Judith Butler and Anne Carson were major influences for de Marcken in the making of this book. At the time of writing, she was reading Butler’s The Force of Non-Violence and was particularly struck by a 2014 talk, ‘Speaking of Rage and Grief’, in which Butler quotes Anne Carson in her preface to Grief Lessons, a translation of four plays by Euripides: ‘Why does tragedy exist? Because you are full of rage. Why are you full of rage? Because you are full of grief.’ De Marcken has described this moment as one that ‘completely unmade and remade’ her, prompting the novel’s guiding question: ‘how much can we lose before we, ourselves, are lost – and then what happens?’ De Marcken’s protagonist wonders something similar in the book: ‘How small or altered or distant must a part of us be before it stops being a part of us? Does it ever?’

In a podcast interview with Tin House, de Marcken elaborates: ‘The book puts intense pressure on the notion of an individual self and what a self is – both in a compositional and decompositional way. It troubles selfhood through accretion and accumulation and also troubles selfhood through loss and removal.’ The novel’s treatment of identity revolves around this very interplay: what is formed, what is unmade. A name appears, then fades. A limb is lost, then replaced or forgotten.

Each time something disappears or slips out of reach, it’s recounted with a certain emotional distance – at first, at least. It’s through the accumulation of these losses, and the emotional weight they carry, that their significance begins to register. The continual loss of body parts experienced by the zombie characters provides the most visceral example of this. At first, the protagonist’s lost arm is treated with detachment (literally and emotionally). ‘Janice 2 picked it up and brought it back to the hotel. I would have thought it would affect my balance more than it has. It is like getting a haircut’. The tone here is oddly casual, almost clinical. Even the language shifts: ‘My hand. My wrist.’ Then simply, ‘the fingernails’. Not ‘my fingernails’.

This stands in stark contrast to how bodily disintegration is typically portrayed in literature and film – as a site of horror and a metaphor for the collapse of identity. In Cronenberg’s The Fly, scientist Seth Brundle undergoes a horrific metamorphosis into a fly, or the ‘Brundlefly’ as he calls it. As his limbs and teeth fall away, his mind remains painfully aware, clinging to whatever fragments of humanity it can, until the very end. In Kafka’s Metamorphosis, salesman Gregor Samsa clings to his routine even as he becomes a giant insect, attempting to get to work on time and actively listening to the sounds of his sister’s violin. These stories suggest: to lose the body is to lose the self.

But do we need the body to be ourselves? In de Marcken’s world, maybe not. Mitchem loses his penis, Marguerite her breasts, and eventually, the protagonist loses her head. They continue to exist but their losses appear to haunt them in strange and dim ways. At one point, the protagonist recalls – probably imagines – being a child and pretending to be a horse. She used sticks to help herself feel more convincingly equine, similar to how she replaces her head towards the end of the novel. She reflects, ‘It is my human shape that allows me to see myself, feel myself, as a human. Without the arm, it is that much harder.’

This tension – between the self as rooted in the physical body and the self as something that can exist apart from it – speaks to longstanding philosophical questions. Whether you’re in Aristotle’s camp – where the soul is the essential form of the body – or with the dualists, de Marcken isn’t actually concerned with settling debates. Instead, she proposes an in-between state – a version of self that can persist, even transform, despite dismemberment, despite death. For example, at the hotel, Mitchem, the pseudo-leader, pseudo-preacher, holds up a coffee cup: ‘This cup is the body. This cup is the soul […] Therefore the body is the soul’. Even as he says it, he seems unconvinced. But the moment gestures toward the idea that even if categories like body and soul are arbitrary, they remain lodged in our experience of being. And so, we continue to cling, almost instinctively, to the old frameworks that once helped us make sense of it all, like the dead crow the protagonist stores inside her chest in place of a heart. It never becomes part of her. She wants it to be. But as de Marcken says of the crow, ‘It never really works […] it hurts to lose it at the same time.’ Loss, even when followed by substitution, still feels like loss.

Despite the dead crow and the bodily disintegration, not to mention the novel’s entire premise, it still feels surprising when de Marcken veers into horror. This is probably because her prose – gentle, lyrical – is set against acts that are brutal. One particularly gory moment comes after the protagonist, during a bout of aimless wandering, encounters lovers in a field. In a sudden, violent act, she stabs the woman, carving ‘soft belly meat’ and ‘easy cuts from her thigh’, not to eat but to keep. ‘I do not know why I do this except I can’t let go.’ Then she returns to the hotel and removes her clothes, cuts her hair – a ritual of shedding.

Not long after, she embarks on a solitary, fragmented journey. During this time, she reflects on the Donner party – a group of American pioneers who, after being trapped in a brutal winter in the Sierra Nevada, were forced into cannibalism. She focuses on the eerie list of ‘all the things they left along their way across the continent’. As she closes her eyes and repeats the list, urging herself not to forget, a reverence emerges for these forsaken objects. More broadly, characters tend to fixate on objects as a way to find comfort and make meaning. It is after all an acutely human trait to accumulate possessions, to tie memories to them, to tie them to who we are.

But since this is a story about both composition and decomposition, it feels only fitting that, later on, when the protagonist encounters an unnatural hole, she begins to shed her possessions into it – her clothes, her sneaker, her cornflower dress – one item at a time. ‘It is a relief. It’s less a choice than a recognition or an admission’. The final act of dropping the crow into the hole carries the most weight. It’s not the crow’s physical presence that matters – it’s already dead – but what it represents to her. Her grief, therefore, isn’t about the object itself; it’s about her attachment to it. In the end, she discards a stone that she’s carried in her cheek. It’s the final gesture of letting go.

Like the Donner party, she heads west, encountering pirates, and a roving group of people whose travels, unsettlingly, mirror the Donner party’s voyage. Here the gaps in the prose create a drifting feel. Time and space themselves become elastic, bending and shifting unpredictably. In this context, the protagonist’s identity or sense of self feels even less like a fixed entity and more like a series of displacements – fluid, contingent, and perpetually in flux.

This fluidity forces us to confront just how much our sense of comfort and identity is tied to the spaces we occupy – or whether identity can even endure when those spaces lose their physical contours. Banana Yoshimoto’s Kitchen comes to mind. In the novel, Mikage Sakura, who is grieving the loss of her grandmother, clings to domestic spaces and routine for safety and continuity. It’s this cementation in setting that buoys her (and the narrative). Without that anchor, one can only imagine how lost she’d be.

De Marcken’s protagonist doesn’t have this – and in its absence, there is only the weight of emptiness. ‘I am crying even as I think about crying. I think, this is what remains after the swarm. I think, this is emptiness itself. I think it is more the emptiness of a church than the emptiness of an empty home. Big and high-ceilinged and nothing in it belongs to me.’ This is the ache of alienation, of disconnection. Of walking away from places that may never have offered meaning or belonging – and still mourning what they represented. It’s a complicated feeling.

Like the protagonist, I’ve never been good at letting go. Most of us aren’t. I’ve spent my life projecting meaning onto the smallest things: a seashell, the brittle branches of winter trees. I romanticise everything: wind-blown beaches and lonely corner stores. Fitting, then, that my first encounter with the novel came after a Vipassana retreat. Ten days of 13-hour meditations, complete silence (including body language and eye contact), and fasting. I was assigned a number – 244 – and shuffled into a room indistinguishable from all the others: bare walls, thin mattress, a plastic bucket. Our clothes, even, had to be pale and plain. The idea was to strip ourselves of personality, of self. Leave your stories at the door. You’re not you here – you’re 244. During the teachings, we learnt about the idea of ‘upādāna’, or clinging. We were told over and over not to cling to our possessions, to people, to pain. But, surprise, surprise: that’s easier said than done.

Perhaps one of the most significant things the protagonist clings to is ‘you’. This ‘you’ is someone she frequently refers to – recalling memories, expressing regret over things she should have done, and questioning her own identity in relation to this figure: ‘I think of all the time I spent deciding. Imagine what I missed. My whole life. I know again that I missed it all with you’. ‘You’ is likely a former lover, though she can't remember them, of course – not fully.

There’s also an unsettling sense that ‘you’ may not have ever truly existed. ‘It seems impolite to listen, wrong even. Like opening a letter delivered to the wrong address and pretending that the “you” of the letter is really you. You. You can be anyone.’ So ‘you’ may represent a person, or it could represent a feeling – a stand-in for longing or an experience she wishes she had. Within this context, where the ‘you’ is fundamentally unknowable, ‘you’ becomes a product of longing, projection, and eventually grief. This is crystallised in the novel’s final line: ‘The space between me and me is you. This is a mystery’. It suggests that the ‘you’ is both a bridge and a barrier – both intimacy and absence.

There’s similarity here to Rachel Cusk’s protagonist Faye, whose narrative in the Outline trilogy is constructed less from her own story and more from the stories of others. Whilst staying in her new flat, she speaks to the people around her – passively listening to their histories. As Judith Thurman says of Faye, ‘she lends herself as a filter to her confidants, and from the murk of their griefs and sorrows […] she extracts something clear – a sense of both her own outline and theirs.’ Like Cusk, de Marcken experiments with selfhood as a receptive space in which the self is not a fixed, internal essence, but something that flickers into being in relation to others, even if they’re unreliable, imagined, or lost.

On my first reading, I didn’t quite understand this book. I couldn’t grasp how a protagonist could emerge so blank, so unformed – and what that absence meant for the narrative. How could I connect with a character I knew nothing about? But returning to it, it became clear that that emptiness is the intent. This idea of stripping away the self isn’t new; it’s been explored for centuries through religion and philosophy – from the Buddhist notion of anatta, or ‘no-self’, to Descartes’ doubting mind, to mystic traditions that seek ego dissolution. But while these frameworks offer space to contemplate the self’s undoing, it’s much harder to pull off in narrative form, where readers are trained to latch onto character as a stable anchor. When it is executed effectively, however, the result can be both innovative and emotional – as de Marcken’s novel demonstrates. Her refusal to provide a fixed or knowable self forces us to confront something more fragile, and more universal.

In stripping away the familiar markers of identity – place, people, possessions – de Marcken leaves us with the raw, elemental traits we all share. What remains in the absence is what endures: memory, longing, and most of all, loss. This isn’t just about identity, then. It’s about what’s left behind when all else is gone. It’s about the things we attach ourselves to – the things we cling to – as if they could ever hold us together. And often, we do cling. Long after it makes sense. Long after it’s over.