Where is all the Book Data?

Melanie Walsh on (not) publishing data

Melanie Walsh looks at how the data company BookScan hold the power to shape publishing companies, authors, and readers, and the emergence of “counterdata”.

After the first lockdown in March 2020, I went looking for book sales data. I’m a data scientist and a literary scholar, and I wanted to know what books people were turning to in the early days of the pandemic for comfort, distraction, hope, guidance. How many copies of Emily St. John Mandel’s pandemic novel Station Eleven were being sold in COVID-19 times compared to when the novel debuted in 2014? And what about Giovanni Boccaccio’s much older—14th-century—plague stories, The Decameron? Were people clinging to or fleeing from pandemic tales during peak coronavirus panic? You might think, as I naively did, that a researcher would be able to find out exactly how many copies of a book were sold in certain months or years. But you, like me, would be wrong.

I went looking for book sales data, only to find that most of it is proprietary and purposefully locked away. What I learned was that the single most influential data in the publishing industry—which, every day, determines book contracts and authors’ lives—is basically inaccessible to anyone beyond the industry. And I learned that this is a big problem.

The problem with book sales data may not, at first, be apparent. Every week, the New York Times of course releases its famous list of “bestselling” books, but this list does not include individual sales numbers. Moreover, select book sales figures are often reported to journalists—like the fact that Station Eleven has sold more than 1.5 million copies overall—and also shared through outlets like Publishers Weekly. However, the underlying source for all these sales figures is typically an exclusive subscription service called BookScan: the most granular, comprehensive, and influential book sales data in the industry (though it still has significant holes—more on that to come).

Since its launch in 2001, BookScan has grown in authority. All the major publishing houses now rely on BookScan data, as do many other publishing professionals and authors. But, as I found to my surprise, pretty much everybody else is explicitly banned from using BookScan data, including academics. The toxic combination of this data’s power in the industry and its secretive inaccessibility to those beyond the industry reveals a broader problem. If we want to understand the contemporary literary world, we need better book data. And we need this data to be free, open, and interoperable.

Fortunately, there are a number of forward-thinking people who are already leading the charge for open book data. The Seattle Public Library is one of the few libraries in the country that releases (anonymized) book checkout data online, enabling anyone to download it from the internet for free. It isn’t book sales data, but it’s close. And such data might help us understand how the popularity of certain books fluctuates over time and in response to historical events like the COVID-19 pandemic (especially if more libraries around the country join the open data effort). Literary scholars have also begun to compile “counterdata” about the publishing industry. Richard So, a professor of English and cultural analytics at McGill University, and Laura McGrath, an English professor at Temple University, have respectively collected data about the race and ethnicity of authors published by mainstream publishing houses. Through their work, So and McGrath each prove that the Big Five houses have historically been dominated by white authors and that they continue to systematically reinforce whiteness today.

While all of this data is powerful in its own right, it becomes even more powerful if we can combine it all together: if we can merge author demographic data with library checkout data or with other literary trends. This promise anchors the Post45 Data Collective, an open-access repository for literary and cultural data that was founded by McGrath and Emory professor Dan Sinykin, and that I now lead as a coeditor with Sinykin. One of the goals of the repository is to help researchers get credit for the data that they painstakingly collect, clean, and share. But a broader goal is to share free cultural data with anybody who wants to reuse and recombine it to better understand contemporary literature, music, art, and more.

Now, I am pleased to introduce a Public Books series that honors and revolves around the Post45 Data Collective, and that will hopefully add to it and strengthen it. This series, Hacking the Culture Industries, demonstrates how corporate algorithms and data are shaping contemporary culture; but it also reveals how the same tools, in different hands, can be used to study, understand, and critique culture and its corporate influences in turn. Each of the authors in this series takes on a different kind of cultural data—from New Yorker short stories to Spotify music trends, from New York Times reviews to audiobook listening patterns. (Some of the data featured in these essays will also be published in, or is already available through, the Post45 Data Collective, enabling further research and exploration.)

I will say more about this series below, but first I want to focus on the broader significance of the Post45 Data Collective’s mission: to make book data (and other kinds of cultural data) free and open to the public.

To people who care about literature, data is often seen as a neoliberal bogeyman, the very antithesis of literature and possibly even what’s ruining literature. Plus, people tend to think that data is boring. To be fair, data is sometimes a neoliberal bogeyman, it is sometimes boring, and it may in fact be making literature more boring (more on that to come, too). But that’s precisely why we need to pay attention to it.

Corporate data already deeply influences the contemporary literary world, as revealed both here and in the broader essay series. And so, if you care about books, you should probably care about book data.

BookScan’s influence in the publishing world is clear and far-reaching. To an editor, BookScan numbers offer two crucial data points: (1) the sales history of the potential author, if it exists, and (2) the sales history of comparable, or “comp,” titles. These data points, if deemed unfavorable, can mean a book is dead in the water.

Take it from freelance editor Christina Boys, whom I spoke with over email, and who worked for 20 years as an editor at two of the Big Five publishing houses (Simon & Schuster and Hachette Book Group). Boys told me that BookScan data is “very important” for deciding whether to acquire or pass on a book; BookScan is also used to determine the size of an advance, to dictate the scale of a marketing campaign or book tour, and to help sell subsidiary rights like translation rights or book club rights. “A poor sales history on BookScan often results in an immediate pass,” Boys said.

Clayton Childress, a sociologist at the University of Toronto, came to similar conclusions in his 2012 study of BookScan data, in which he interviewed and observed more than 40 acquisition editors from across the country. Bad book sales numbers can haunt an author “like a bad credit score,” Childress reported, and they can “caus[e] others to be hesitant to do business with them because of past failures.”1

According to editors like Boys, the sway of book sales figures has siphoned much of the creativity and originality out of contemporary book publishing. “There’s less opportunity to acquire or promote a book based on things like gut instinct, quality of the writing, uniqueness of an idea, or literary or societal merit,” Boys claimed. “While passion—arguing that a book should be published—still matters, using that as a justification when it’s contrary to BookScan data has become increasingly challenging.” In a similar vein, Anne Trubek, the founder and publisher of the independent press Belt Publishing, told me that BookScan data is a strong conservative force in the industry—one of the reasons, though not the only reason, that Belt Publishing stopped subscribing after only one year. Trubek says that BookScan data encourages publishers to keep recycling the same kinds of books that sold well in the past. “I didn’t want to be a publisher who was working that way,” she elaborated. “That was not interesting. I think a lot of Big Five publishing is driven by data, and I think that things end up much more unimaginative as a result.”

Despite these claims, other publishing professionals maintain that BookScan data has not changed their work quite as dramatically. Childress interviewed one editor who explained that he manages to use BookScan data in creative ways to support his own independent choices.2 Yet even when editors find inventive ways to use BookScan data and to preserve their own aesthetic judgment, it is striking that they must still use and reckon with BookScan data in some form.

Perhaps most importantly, however, it is likely that books end up much more racially homogenous—that is, white—as a result of BookScan data, too. For example, in McGrath’s pioneering research on “comp” titles (the books that agents and editors claim are “comparable” to a pitched book), she found that 96 percent of the most frequently used comps were written by white authors. Because one of the most important features of a good comp title is a promising sales history, it is likely that comp titles and BookScan data work together to reinforce conservative white hegemony in the industry.

For all of its extensive influence, most of us outside the publishing industry know surprisingly little about BookScan data: how much it costs, what it looks like, or what exactly it includes and measures. According to a 2009 business study,3 publishing house licenses for BookScan data cost somewhere between $350,000 and $750,000 a year at that time. Literary agents, scouts, and other publishing professionals can subscribe to NPD Publishers Marketplace for the humbler baseline price of $2,500 a year, and many authors can view their own BookScan data for free via Amazon.

But academics and almost everyone else are out of luck. When I inquired about getting access to BookScan data directly through NPD Group (the market research company that bought US BookScan from Nielsen in 2017), a sales specialist told me: “There are some limitations to who we are permitted to license our BookScan data to. This includes publishers, retailers, book distributors, publishing arms of universities, university presses and author agents. Do you fall within one of these categories?” When I reached out to NPD Publishers Marketplace, they told me the same thing. David Walter, executive director of NPD Books, confirmed that NPD does not license data to academic researchers: “We only license to publishers and related businesses, and … our license terms preclude sharing of any data publicly, which conflicts with the need to publish academic research. That is why we do not license data for the purposes of academic research.”

This prohibitive policy seems to be a reversal of a previous, more open stance toward academic research, since scholars have indeed used and written about BookScan data in the past.4 Walter declined to comment on this about-face, but the change of heart is certainly disheartening.

While it’s not completely clear why BookScan changed their minds about academic research, it is clear that BookScan numbers, despite their significance and hold on the marketplace, are not completely accurate. BookScan claims to capture 85 percent of physical book purchases from retailers (including Amazon, Walmart, Target, and independent bookstores) and 80 percent of top ebook sales. Even so, there’s a lot that it doesn’t capture: direct-to-consumer sales (which account for an estimated 25 percent of Belt Publishing’s sales), as well as books sold at events or conferences, books sold by some specialty retailers, and books sold to libraries. BookScan numbers aren’t just conservative, then, but incomplete.

To what extent might BookScan data—with all of these holes and inaccuracies—be shutting out imaginative and experimental literature? To what extent might BookScan data be shutting out writers of color—or anyone, for that matter, who doesn’t resemble the financially successful authors who came before them?

To fully answer these questions, we would need not only BookScan data but other kinds of data, like the race and gender of authors. Until recently, this kind of demographic data did not exist in any comprehensive way.

This is why Richard So and his research team set out to collect data of their own. They began by identifying more than 8,000 widely read books published by the Big Five houses between 1950 and 2018, and then they carefully researched each of the authors and tried to identify their race and ethnicity. As So and his collaborator explained in a 2020 New York Times piece, “to identify those authors’ races and ethnicities, we worked alongside three research assistants, reading through biographies, interviews and social media posts. Each author was reviewed independently by two researchers. If the team couldn’t come to an agreement about an author’s race, or there simply wasn’t enough information to feel confident, we omitted those authors’ books from our analysis.” After this time-consuming curation process, So was able to demonstrate that 95 percent of the identified authors who published during this 70-year time period were white, a finding that quickly went viral on Twitter. Of course many people already knew that the publishing industry was racist, but these data-driven results seemingly struck a chord on social media because they revealed the patterns in aggregate. While So’s valuable, hand-curated demographic data is currently embargoed, it will eventually be published through the Post45 Data Collective,5 which means that it will be available to anyone and mergeable with other kinds of open data, such as library checkout data from the Seattle Public Library.

Since 2017, the SPL has publicly released data about how many times monthly each of its books has been borrowed (from 2005 to the present), as well as whether the book was checked out as a print book, ebook, or audiobook. Importantly, all individual SPL patron information is scrubbed and de-identified.

For this unique dataset, we owe thanks primarily to two people: David Christensen, lead data analyst at the SPL, and Barack Obama. In 2013, President Obama signed an executive order that all federal government data had to be made open, and soon many state and local governments followed suit—including, in 2016, the City of Seattle, which required all of its departments to contribute to the city’s open data program. While many public libraries participate in similar open data programs, most contribute only minimal amounts of data, such as the total number of checkouts from a branch over an entire year. Most libraries don’t have the staff or resources to share anything more substantial. Most also don’t have Christensen, the SPL’s “open data champion,” who advocated for sharing as much data as safely possible.

Safety—more specifically, privacy—is another reason that most libraries don’t share this kind of data: because they have long-held traditions of doggedly protecting patron privacy, making them reticent to collect and release swaths of circulation-related information on the internet. Twenty years ago, for example, the Seattle Public Library was not collecting any checkout data about individual books or patrons. (I had to clarify this point with Christensen. Wait, like, nothing? The Seattle Public Library wasn’t collecting any data about titles or patrons at all? Yep, nothing.)

If you’ve been paying attention to the dates here, you might be wondering: If the SPL only started collecting data in 2017, how do they have borrowing data that stretches back to 2005? It’s a good question. It turns out that while the SPL system itself was not collecting any data between 2005 and 2017, somebody else was, and that somebody was storing the data in an unlikely place within the library itself: in an art installation that hangs above the information desk on the fifth floor. This installation, “Making Visible the Invisible,” was created in 2005 by artist and professor George Legrady, and it features six LCD screens that display real-time data visualizations about the books being checked out and returned from the library.6 Somewhat miraculously, the SPL was able to mine this art installation to recover 10 years of missing, retroactive checkout data.

The many ways that SPL checkout data might be used to understand readers or literary trends are still relatively unexplored. In 2019, The Pudding constructed a silly “Hipster Summer Reading List” based on SPL data, highlighting books that hadn’t been checked from the SPL in over a decade (a perversely funny list but definitely a terrible poolside reading list).

This checkout data is also used internally for a variety of purposes, including to make acquisition decisions, as SPL selection services librarian Frank Brasile explained. But the factor that apparently influences library acquisitions the most is simply what the Big Five choose to publish. “We don’t create content,” Brasile reminded me in a somewhat resigned tone. “We buy content.” To a large extent, then, public libraries inherit the pervasive, problematic whiteness that is endemic in the publishing industry.

Corporate distributors for public libraries are, in fact, already swooping in and capitalizing on the need for data-driven diversity audits. Last year, Ingram launched inClusive—“a one-time assessment service to help Public Libraries diversify their collections by discovering missing titles and underrepresented voices”—while Baker & Taylor and OverDrive unveiled their own diversity analysis tools.7 When I spoke with Brasile, the SPL was partway through one such diversity audit and about to begin another.

The emergence of these audits—almost certainly expensive and with dubious understandings of diversity—makes the significance of open book data even more stark. If we could combine So’s author demographic data with library catalog data, for example, then librarians, academics, journalists, and community members might be able to participate more fully in these audits and conversations, too—and without paying additional, imperfect gatekeepers for the privilege.

Making data publicly available is only the first step, of course. Making meaning from the data is the much harder next leap. What, if anything, can we actually learn about culture by studying data? What kinds of questions can we actually answer?

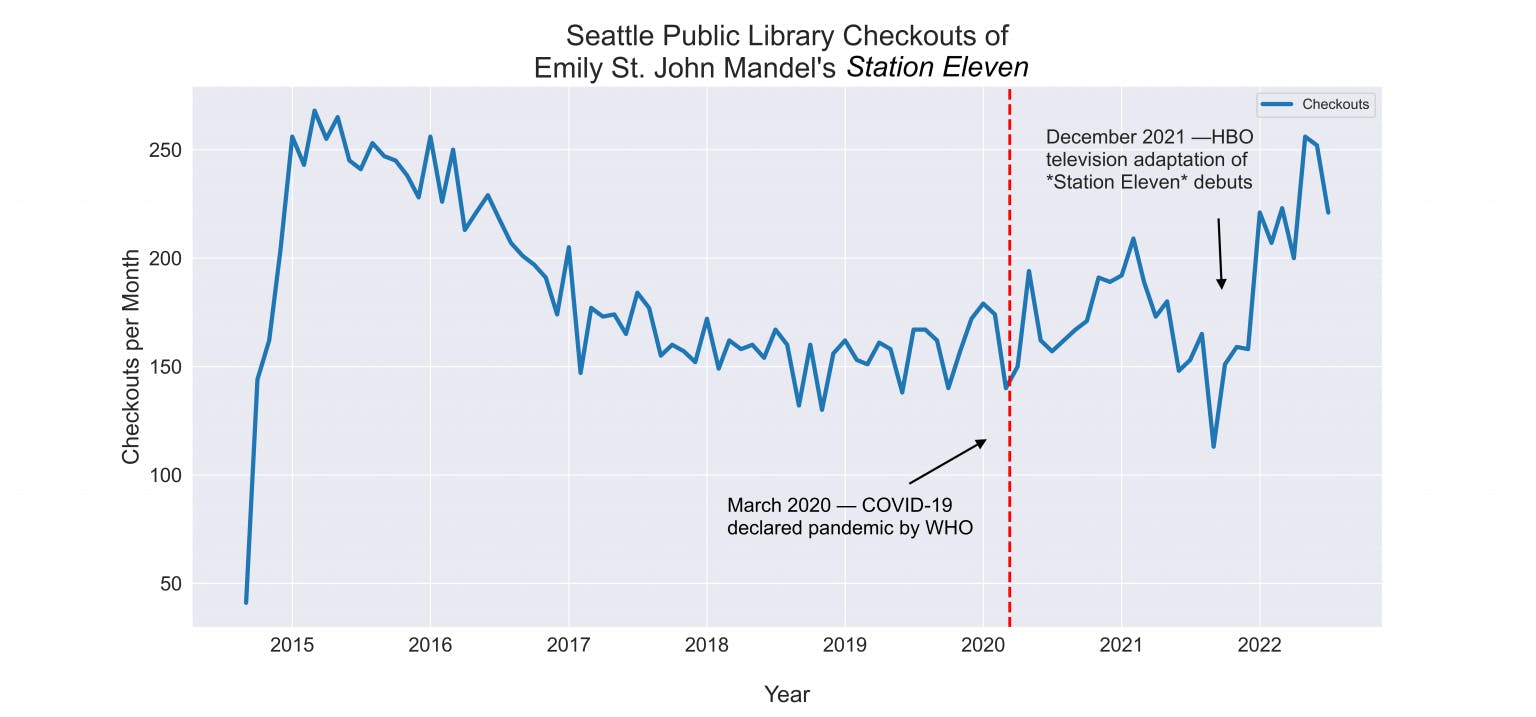

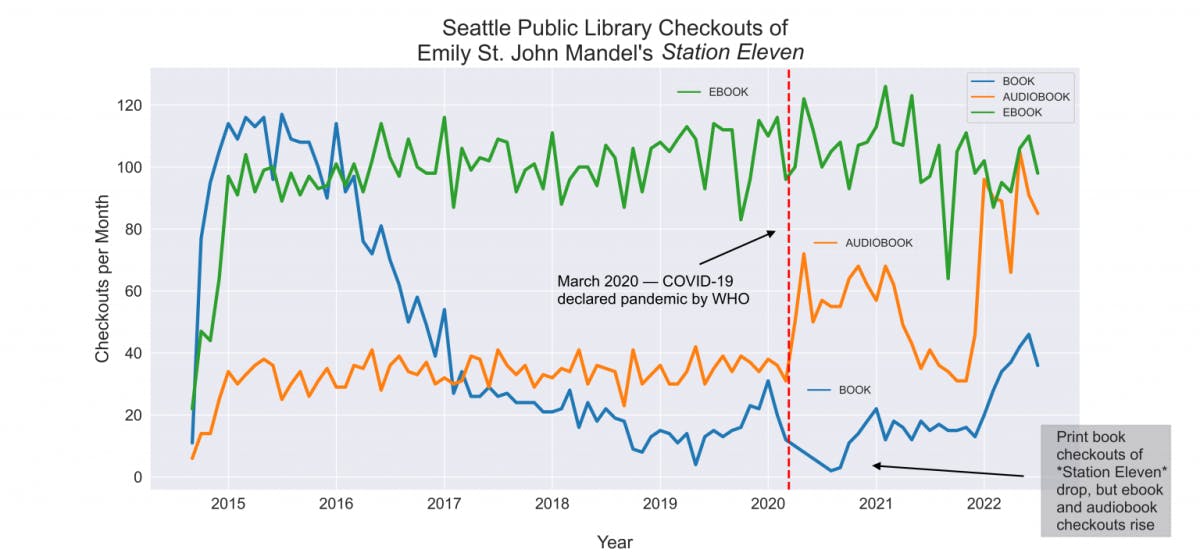

For a start, we can begin to answer some of the questions that I posed at the outset about whether people were clinging to or fleeing from pandemic stories in the early days of COVID-19. If we use open SPL circulation data in lieu of proprietary book sales data, we can see that Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven was not as popular in the first days of the pandemic as it was when it debuted (though it almost reached its record borrowing peak this May, perhaps aided by the HBO television adaptation of the novel that aired earlier this year). We also need to consider the fact that SPL branches physically closed their doors in March 2020. Ebook and audiobook checkouts of Station Eleven both reached all-time highs post–COVID-19.

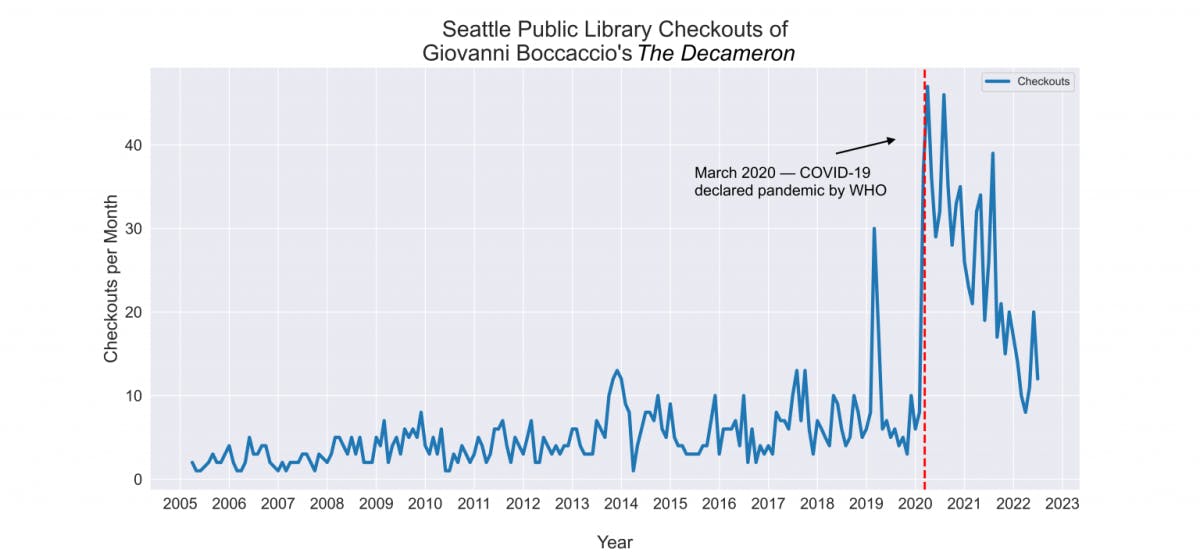

And though Boccaccio’s The Decameron has been less popular than Station Eleven overall, it saw an even more dramatic rise in circulation after March 2020.

So in the wake of COVID-19, it seems that Seattle library patrons have indeed been seeking out pandemic tales. In fact, thanks to the data, that’s something we can track at the level of the individual title and month.

The rest of the essays in this series offer even more compelling testaments to the insights that can be gleaned from cultural data. Drawing on a year of audiobook data from the Swedish platform Storytel, Karl Berglund takes us on a deep dive into the idiosyncratic listening habits of specific (anonymized) users. In so doing, Berglund maps out three distinct kinds of reader-listeners, including the kind of listener—a “repeater”—who consumes Stieg Larsson’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo trilogy every day, over and over again.

These audiobook “life soundtracks,” as Berglund refers to them, are somewhat akin to Spotify’s mood-driven “vibes” playlists, a musical innovation examined by Tom McEnaney and Kaitlyn Todd through the playlists’ acoustic and demographic metadata. What the researchers find is that these new “vibes” playlists feature younger, more diverse artists than traditional genre playlists like country or hip-hop, but they are also quieter and sadder (“soundtracks to subdue,” as the authors put it).

While McEnaney and Todd call our attention to the manipulative maneuvers behind Spotify’s algorithms, Jordan Pruett explores the artifices behind the New York Times’ famous bestseller list (an investigation that pairs well with the NYT bestseller data that he curated and published in the Post45 Data Collective). Pruett lays bare how the seemingly authoritative list has long been shaped by distinct historical circumstances and editorial choices.

The last three essays all tackle important issues of cultural representation by turning to numbers. Howard Rambsy and Kenton Rambsy examine how, and how often, the New York Times discusses Black writers. They offer quantitative proof of the frequently leveled critique that elite white publishing outlets often cover only one Black writer at a time, and they show that this is especially true with writers like James Baldwin, Toni Morrison, and Colson Whitehead.

Nora Shaalan explores the fiction section of the New Yorker, especially the view of the world imagined by its short stories over the past 70 years. Despite pretensions toward cosmopolitanism, the magazine, Shaalan reports, largely publishes short stories that are provincial, both domestically and globally.

Finally, Cody Mejeur and Xavier Ho chart the history of gender and sexuality representation in video games, both in terms of who is portrayed in games and who makes them. Today, the common line is that games have become more inclusive. But, as Mejeur and Ho reveal, whatever inclusiveness does exist is driven by indie producers on the margins—and there’s considerable obstacles still to overcome.

The essays of Hacking the Culture Industries, when considered together, demonstrate that the future of human culture is already being determined by data. They also show that to understand this future and to have a chance at reshaping it, we need to care about data. We need to know where all the important cultural data is, who controls it, and how it’s being used.

We also need to create, share, and combine counterdata of our own, not just to understand what’s going on with contemporary culture, but also to fight back against the powers that threaten it. Big corporate data is currently poised to make literature and culture more unequal, more restrictive, and more conservative. To reverse the tides—to make culture more equitable, more inclusive, and more imaginative—we may need to start by hacking the culture industries.