For the Life of Faith

Miles Pattenden on Catholicism's gendered draw

Miles Pattenden reviews two biographies of Catholic women – a former member of Sydney's Protestant elite and an Armadale order of nuns. What did they give up for the Church? And what did they have to gain?

Catholicism has always been a part of Australian identity. Irish convicts arrived on the First Fleet. The colonial administration recognised a mission to New South Wales in 1820. The grand cathedrals in Melbourne and Sydney rose, stone by stone, not long after. Australian Catholicism was brash, optimistic, triumphalist then. Above all, and deep into the twentieth century, it was growing. By 1900, one in five Australians was Catholic. In the 1960s, well over one in four. The Irish-born Archbishop of Sydney Patrick Moran became Australia’s first cardinal in 1885. His successors were major figures not only in Church but ‘of state’. Witness the notoriety afforded to Daniel Mannix and George Pell. The Australian Church embodied ‘Ireland’s Empire’, as the historian Colin Barr has put it – a Faustian pact struck between bishops and secular power which kept the former in riches and society’s dregs under control.

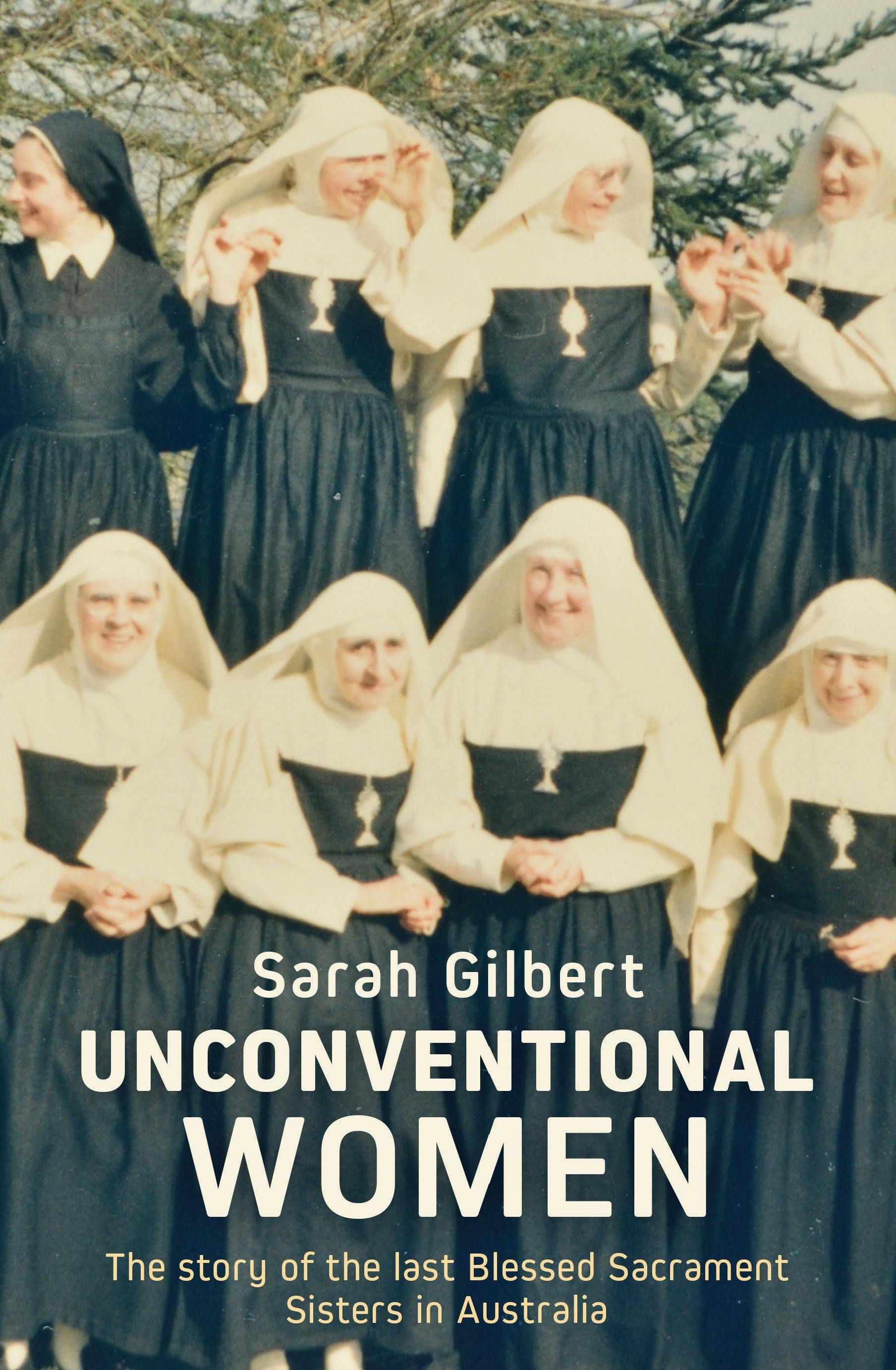

Australia’s Catholic history is often told in the manner set out above: as institutional and demographic. Think of Patrick O’Farrell’s celebrated history, The Catholic Church and Community in Australia, published in 1977. How refreshing it is, then, to encounter two authors who eschew such formal focus on politics or hierarchy and instead take up Edmund Campion’s exhortation to examine what being Catholic meant to Australian inner lives (Australian Catholics, 1988). That Patrick Mullins and Sarah Gilbert do so in these two books by interrogating the experiences of women – typically a neglected group in this sort of historiography – is all the more invigorating.

Yes, Mary McKillop sits alongside Moran, Mannix, Pell, and other male luminaries as a token female figure in the annals of Catholic Australiana. Mary Glowery gets her cameos too, though her major philanthropic contribution was to India not the land Down Under. Caroline Chisholm, a nineteenth-century convert who turned her life towards humanitarian causes, and Mary Kate Barlow, who settled in Sydney in 1884, might be included as well to boost the count. There are others. And though these pious female Catholics were, almost by definition, exceptional – they translated their fervent faith into urgent action – their biographies perpetuate a hoary narrative of ‘great individuals making History’. Historians today are sceptical of such hagiography. They want to know how societies and systems operate through the values, beliefs, and interactions of the many.

The further turn in these books to a social and cultural history of Australian Catholic lives is therefore most welcome. They also tell a quite specific and time-honoured tale of the gaining and losing of faith. One woman’s quixotic embrace of a creed marginalised her in high society. Many women lost their social world when their convent dissipated around them. Some began to question the entire legitimising theological system which had justified it in the first place.

Catherine Mackerras (1900–77), who is the subject of Patrick Mullins’ short but engaging volume, was, in some ways, an unexceptional member of Sydney’s Protestant elite – at least until she chose to become a Catholic. Intelligent, articulate, educated: her life would doubtless have looked very different in the contemporary age. Perhaps she would have been high up in government, the civil service, or the academy. As it was, the young Catherine was forced to endure post-colonial Sydney’s stifling conformity and her Presbyterian father’s anti-Catholic, anti-religious prejudices. At Sydney University, she met her husband Alan, bonding with him over their mutual love of ideas and poetry. The couple lacked her parents’ financial resources and could not command the high social status of her paternal grandfather, sometime politician and University Chancellor Sir Henry Normand MacLaurin. Catherine’s parents helped the young couple out, buying them a house in Vaucluse. But material wealth does not seem to have been enough to sate the strong-willed and romantic Catherine. In Divided Heart, the memoir that this book critiques, she claimed to have been inspired from an early age by the bells of St Mary’s Cathedral (a Sydney landmark not yet complete at that time). A yearning for order, for beauty, for meaning pervaded her innermost sentiments with growing intensity. She eventually decided only conversion to the Catholic Church could fill the void, to her husband’s horror.

Unlike Catherine Mackerras, the heroines of Sarah Gilbert’s work are mostly working class. Vianney Hatton came from the then less-than-fashionable Bondi. Maureen Flood grew up in hotels in country New South Wales. Barbara Fingleton and Marie Grunke hailed from farms. Monica O’Leary had a modest background in Adelaide. The Servants of the Blessed Sacrament brought these women together – an order of nuns focused obsessively on Eucharistic adoration, founded in 1850s France by Peter Julian Eymard, a priest, and Marguerite Guillot, a nun. Its sisters aspired to be contemplatives who spoke only when required. The 1950s Melbourne chapter manned a continuous roster of perpetual prayer in the chapel before the Eucharistic Host. They made money by baking wafers for distribution in churches throughout Victoria. The business was successful and only grew with the state’s burgeoning Catholic congregations. There was little time for a fledgling nun to stand still. Work was everything, second only to Jesus.

Gilbert interviews many of the surviving sisters to record their voices faithfully. Each has an interesting, sometimes heartbreaking, story about why she joined. For Vianney, it just seemed natural to enter the convent after spending her childhood in Catholic boarding schools. For Jill Thomas, her decision was a reaction to the untimely deaths of two schoolfriends. For Melissa Jaffer, the convent offered a home to which to withdraw from worldly chaos. For Marie Grunke, it was a place to forget a tragic love affair in New Zealand and the baby she lost to adoption. The conventual life these women entered was a far cry from the liberating space which Catherine Mackerras created for her spirituality. The nuns lived by a strict rule of obedience. Reason and learning were discouraged. Penances were arbitrary, severe, and often humiliating. Vianney once tried to smuggle out notes to her family and friends hidden in little pamphlets she had been allowed to forward to them. Mother Superior discovered the subterfuge and made her kiss the feet of the first three sisters who came through the door that night.

Loss is a major theme of both these books: what had to be given up for the life of faith. In Mackerras’ case a place among Sydney’s Protestant elite was the most conspicuous sacrifice she had to make. But, as society’s sectarian tensions diminished, its edge may have worn off. Far worse was the rupture it caused in her marriage. Her husband simply did not understand Catholicism’s appeal. Protestantism was a part of his identity, his own grandfather having repudiated the Catholic Church in order to make his way in Sydney. For his wife to hasten back towards Rome felt like a retrograde step. Then there were practical matters: for example, how were the couple to raise their children? The Catholic Church insisted that those born to Catholics must be inducted into the faith. That would erase Protestantism from the Mackerras line. Catherine’s conversion humiliated her husband, which is surely why there is so little mention of him or his views in her memoir. A deal was struck in the end: their children would be educated as Catholics but encouraged to make up their own minds as adults.

The price of entry was somewhat different for the girls who stood before the cloister door on Hampden Road, Armadale. Progressively, over a number of years, they had to give up all contact with the outside world. Cherished bonds with friends and family suffered. Jill’s father refused to speak to his daughter again if she threw her life away like this. ‘It’s like a death in the family,’ Barbara’s father told acquaintances, melancholically. Boyfriends too were perplexed – though the greater astonishment may lie with Gilbert’s readers when they discover such young men in the nuns’ lives. Not only did Marie have her Kiwi paramour, but Jill went out with Bill for a whole year before telling him, ‘Right… I’m joining the convent in November.’ Postulants – that is the new recruits in their first phase of admission – could still see their families from time to time but were separated from them by a half-height wall and a metal grille. Raising the grille to allow an embrace was a concession and did not happen frequently.

Other rules for social interaction were enforced strictly, the more so as postulants became novices and then fully professed sisters. Missives home were cut in length, and number, over time. Mail received was distributed but once a week. Supposed creature comforts disappeared. Mother Superior was scandalised when Vianney asked for sugar in her tea. ‘They got sugar for me – but that was the end of it. After that time there was no sugar.’ Baths and even the washing of hair had to be preapproved. A sentiment that ‘everybody had to be the same’ prevailed. Sisters ate in silence, one of their number chanting monotonously from a spiritually suitable book. They did the work assigned to them, even when it was pure drudgery. Most found life hard, empty, and depressing. Few were willing to admit that they wanted to leave – yet it was just as hard to tell themselves that they wanted to stay.

Today, we might well call the Order of the Blessed Sacrament’s regime abusive. The Armadale convent had all the hallmarks of a cult: the isolation of the individual, demands for blind adherence, arbitrary and rigid practices. We might even label such a program conversion therapy. Though this term is nowadays associated with evangelicals desperate to cure their sons and daughters of homosexual abomination, similar techniques for dealing with recalcitrant youth flourished in many a pre-Vatican II convent: sisters were taught to, indeed disciplined into, sublimating their inner selves. Banality of process was their truest goal. At weekly public examinations of conscience, so-called ‘Chapters of Faults’, they would gather to confess their sins and to receive lectures on the Order’s constitutions. Infractions were always petty: raising one’s eyes to peer through a window, peeking at food in the kitchen, being personal during recreation time. ‘The first time I went to the Chapter of Faults, somebody came forward and accused themselves of lacking in modesty, and I thought, “I don’t want to hear this! What’s all this about?”’ (Vianney). ‘I think I wasn’t really quite properly prepared for what I actually did walk into… There were very, very strict rules’ (Maureen). ‘Sister Mary Philomena accused Sister Peter Julian of looking at the mirror’ (Jill). Mother Superior and the Novice Mistress seem genuinely to have seen themselves as angels of mercy rather than agents of atrocity, which is how we might all too easily perceive them for their incessant bullying of the younger, impressionable women. ‘There was no fulfillment,’ Jill adds. ‘You couldn’t get ahead.’

Mullins also understands his work as analysing a conversion narrative. And yet, Catherine Mackerras’ conversion – at least as Mullins apprehends it – could scarcely have been more different from the type inflicted upon the cloistered sisters. Mackerras’ spiritual journey was, in Mullins’ presentation, intensely personal. Where the sisters in Gilbert’s book fought to suppress their true selves, Mackerras discovered her true self and became authentic to it. In a somewhat surprising move, Mullins compares her transformation to George’s in Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man and Ennis del Mar’s in Annie Proulx’s Brokeback Mountain. This queering of Catholicism is certainly bold. Yet it is not necessarily unjustified: throughout the early twentieth-century Anglosphere, to dabble in popery was indeed to be ‘out of step’, backwards, outdated – the classic markers of alterity invoked by queer theorist Carolyn Dinshaw. The status of Catholics in Australia changed during the arc of Mackerras’ long life, but only slowly. At the time of Mackerras’ death – and perhaps even when her memoir was published fourteen years later – the sectarian and class divisions which had made Catholicism anathema to the polite were still not fully healed.

Renewed enthusiasm concerning Mackerras, the existence of which Mullins’ effort attests to, is a curious phenomenon. Today, Mackerras’ strained, plummy, Home Counties-esque accent (which one can hear in recordings from the 1970s) might strike one as affected, for by that time, deference to Britishness and British tastes had receded. She stands out not for her impetuous abandonment of the ‘faith of her fathers’ but as a fossilised relic of an antiquated Australia that is no more. Perhaps the extraordinary talents and successes of her various children (including the conductor Charles Mackerras) explain why her name remains on so many lips. But the desire to revisit her story also springs from a certain romanticism. A remarkably accomplished woman broke with convention: that, more than her Catholicism, speaks to contemporary values.

Gilbert’s book could be said to have a broader scope than Mullins’ because it goes beyond its initial story to explain not just what the nuns gave up to join their convent but also what they lost all over again when its life fell apart. As with bankruptcy, per Hemingway, their communal life frayed gradually then vanished suddenly. The Second Vatican Council (1962–65), that exalted Roman jamboree which changed the Church’s face and heart, was the major catalyst. Pope John XXIII may not have known what he was ushering in. Yet, for communities such as Melbourne’s Servants of the Blessed Sacrament, Vatican II’s reforms provided an existential shock to their old ways of life. Routine and ritual were swept away as fast as the sisters’ archaic (and entirely impractical) habits. A new spirit of inquiry, informality, humility was instituted and encouraged throughout the Church. How far the Pope himself led proceedings and how far he felt obliged to follow the impulses of the faithful scarcely mattered. Even secluded nuns were expected to adopt it and adapt.

Vatican II’s story is often presented as one of liberation for the female religious. They were able to cast off burdensome, limiting robes of modesty. They dressed like normal Christians once again, doing good works as they moved once more among them. They set unquestioning obedience aside in favour of independence and intellectual inquiry. All this was the making of many a nun – including some, though not all, of the sisters in Gilbert’s book. Maureen became a writer and theologian. Vianney studied abroad. Marie eventually contacted, and made peace with, her long-lost son. For these three, the positive changes were genuine and brought about a personal spiritual Renaissance. But, for other sisters, zealous reform had adverse effects. Many had been so thoroughly institutionalised that the new freedoms bewildered them. Some never adapted, shell-shocked that a cause to which they had given their lives had simply been declared defunct. Coping was a very real problem. In denial, they even refused to accept the relaxations of strictures forced on them.

Australia’s Servants of the Blessed Sacrament never recovered from the blow Vatican II meted out on them. New recruits dwindled. Existing nuns found that they actually enjoyed normal life and began to leave. These problems were not unique to Australia. The Order itself has been in persistent retreat across its old centres in France, Canada, and the United States. Equally, Vatican II, the harbinger of this decline, was not its root cause. The 1950s and 1960s saw new opportunities for women open up across the Western world. Entry into the post-World War Two workforce, and the pill, fractured the old binary choice of motherhood or the cloister. Sisterly vocation had appealed to women who wanted status but did not much want to become wives and mothers: it had offered an attractive route to responsibility, authority, and education. But now there were other, less arduous routes to those same things. Even the decidedly anti-intellectual convent at Armadale, which had benefitted from the broad effect of women seeking to better themselves, now also lost out from the new paradigm.

The Armadale sisters’ final chapters are potentially sorry ones. Toward the end of the 1970s, their community split into those who preferred to remain cloistered and contemplative, and those who wanted to go out into the world and do practical good. The latter group moved to Sydney, but they also eventually ceased living together as a community. The convent house they acquired in Newtown had too many visitors and disruptions. Individual nuns, having seen via their travels and adventures what it was like to have their own private space, were reluctant to give it up. With no new sisters joining them, most also saw the writing on the wall. As they aged, and their health deteriorated, they connected with the wider world more and with each other less and less. A phone call here, a funeral there. The convent’s winding up was orderly and was made easier by the fact that the Sisters had acquired a useful set of financial assets from all that baking of Eucharistic breads. Today, only two sisters remain: Marie and Marian McClelland, a later arrival to the Order in 1974. Marie lives near her son in rural New Zealand. Marian is alone in Melbourne. The days dwindle for both of them. As Marie puts it, ‘We faced the fact that we’re dying as an order and we were okay with that when we came to terms with it. And so it’s similar to having the headstones done. We’re the last ones!’ By the end, some of the nuns even seem to have lost their faith in God.

An irony of Mackerras’ life is that in converting to Catholicism she lost her voice as much as any of the Armadale sisters. Indeed, Mullins makes much of the silence she imposed on herself during her own, and her husband’s lifetimes – for his sake and perhaps also that of her children. A memoir which communicates as much by omission as it does through inclusion is vulnerable to being ventriloquised – and Mullins is alive to this possibility: we can never be truly sure what Mackerras is telling us. But what does his account reveal about Catholicism’s gendered draw in mid-twentieth-century Australia? And what does Gilbert’s? The women they write about were, for the most part, lively and unconventional. They wanted something different, even if they weren’t quite sure what. The options open to them in that closed, provincial world were limited. They could not strike out as we do today. Becoming Catholic or taking the veil seem to have been attractive options precisely because they were ways to stand out yet still fit in. No one likes a tall poppy. Was that what motivated them to make their choice?

A further answer also suggests itself, though it may be one that neither author would necessarily recognise in their subject. Mackerras and the Armadale sisters all had highly over-developed social consciences. Mackerras may have focused hers on her children and on her desire to improve Australian artistic and cultural life, but women like Vianney, Marie, and Maureen quickly took up every righteous cause going. Their passion to do good guided them to some unlikely places in their lives, among them, campaigns for Indigenous rights and against climate change. What we forget now is that, for good or ill, in their youth the Catholic Church was a vessel – often the prime vessel – for such hopes. After seventy years and countless crises and scandals it may now sound absurd, but people once admired Catholicism for the order it imposed on the world around it. It had resources and clear-sighted solutions. People were yet to see its operations as mere chimera. Were women more likely to see the Church idealistically? Perhaps so, if only because for men it still offered more of a career via the greasy pole of its global hierarchy. Of course, Protestant Australians also projected the same beneficent character onto their Churches, not to mention the British Empire. Gilbert and Mullins are each skilled in presenting such observations unobtrusively, sympathetically, letting their subjects speak for themselves. Gilbert, in particular, makes an eloquent, if understated, case for why oral history remains our best, most authentic way to capture a recent past which is beginning to fade from memory. The challenge is always to separate out the lost then from the nostalgic now. These two books are worthy efforts in that eternal enterprise.